James Graham: was Graham Street, Port Melbourne named after this man?

by Margaret Bride

![Detail, Plan of allotments marked at Sandridge in the parish of South Melbourne [cartographic material] / surveyed by Lindsay Clarke Assit. Surr., 1849. State Library of Victoria.](https://www.pmhps.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Sandridge1849Detail-560px.png)

In 1849 the government surveyor published a Street Plan of Sandridge showing a simple grid of streets with six blocks bounded by the newly named streets of Rouse, Graham, Stokes, Nott and Dow, names that have remained to the present day. Chosen in pre-gold rush times, these names reflected a very early stage of growth in the settlement of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales. So far no documentation has been found to explain the origins of these street names.

However it is likely that they were meant to reflect the status of Sandridge as an arrival and departure place, where merchants built warehouses and where wool, the major source of the wealth of the colony, was loaded onto the ships moored in Hobson’s Bay. In The Borough and its People (page 13) I wrote that it was possible that Graham Street was named after the merchant James Graham although there is no written evidence to support this theory. So who was James Graham?

James Graham was a merchant, dealing mainly in wool who came overland to Melbourne from Sydney as a young man in 1839. He was employed in Sydney by the wool buyer, Stuart Donaldson, who bought a town block of land in the newly settled Port Phillip District. Donaldson needed someone to manage his new property and to act as his wool agent there. The young James Graham accepted this challenge; he was only twenty at the time.

Inspired by a spirit of adventure, James had emigrated from Cuper near Edinburgh to Sydney in 1836. He was a devoted son of Dr. James Moore Graham, to whom James wrote in great detail and with a wry sense of humour. These letters have been preserved and are a source of information on the earliest years of the Port Phillip District, first settled in 1834. Upon his arrival in Melbourne Graham writes to his father saying how pleased he is to have a barrel of oaten meal from which he makes porridge

… and I was acknowledged as the best maker of it in the Colony. If I succeed as well in Mercantile matters as I have done in this you may have no fears for me.

He certainly did succeed in ‘Mercantile matters’. In addition to his work for Donaldson, he immediately acted for J.D.L. Campbell who had travelled from Gravesend to Sydney on the same ship. James was the trusted agent of a number of the sheep graziers, providing them with many of the financial services normally provided by a bank in return for the exclusive right to sell their wool clip. He imported sugar, tea and tobacco as well as selling wool, mainly to English markets. Unlike a number of the earliest businessmen in the colony, he was conservative in the investments he made for himself and his clients, and therefore survived the deep depression of the 1840s relatively unscathed. In his letters he tells his father that he had found suitable sand dunes for a game of golf, which makes me speculate that he might have been one of the young Scottish gentlemen who hit balls around on the dunes later known as Fisherman’s Bend. He certainly enjoyed his early days:

Oh! The bush life is a glorious independent one with room to roam wherever you choose and do whatever you like with nothing to annoy you or stonewall fences or ‘Notice trespassers will be prosecuted’ to stop your ramblings.

When the Melbourne Club was formed in 1839, James was a very early member and remained so until his death in South Yarra in 1898. Paul de Serville, in his history of the Club published in 2017, had access to the substantial archive of Graham’s correspondence, from which he describes Graham’s life in his mature years. James Graham became club president of the Melbourne Club in 1865 and de Serville comments that he was later called the Bismarck of Melbourne merchants. This is followed by a long explanation of this rather strange title. James Graham’s letters to local pastoralists form a unique collection, a mixture of professional advice, commercial news, and gossip about friends in common.

De Serville continues on page 79 of his book:

He became executor of their estates, and in time he joined the boards of many companies. Graham acquired the art of survival, not easily learned in a colony as turbulent economically as it was politically and socially. Economists used to the broad approach have tended to describe the period between 1860 and 1880 as years of steady growth. Graham’s letters paint a different picture: small but sharp changes in the price of wool; tightness of money; alterations in the rental market; unemployment; individual and company insolvencies and minor recessions. The tone of the letters is more pessimistic than optimistic. Graham was above all a realist. In one way Graham revealed himself as an optimist: he sired eighteen children – of whom eleven survived – by his wife Mary Alleyne Cobham … and he gave the great south window at St Paul’s cathedral in his wife’s memory.

De Serville concludes this section by saying that Graham was the leading figure in the pastoral-mercantile establishment of Melbourne and one of the few pioneer merchants to survive and prosper over fifty years.

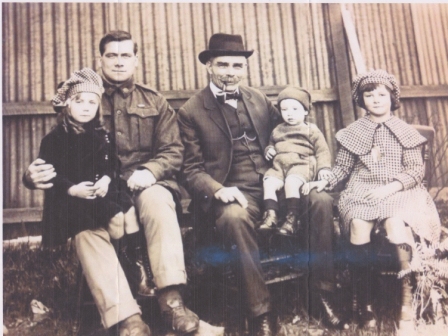

Images of James Graham are from Melbourne Club: a social history by Paul de Serville.

References:

Sally Graham: Pioneer Merchant: the letters of James Graham 1839-1854; Hyland House, South Yarra, 1985

“Graham, James (1819-1898)” by Frank Strahan in Australian Dictionary of Biography accessed on line at https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/graham-james-3650.

Paul de Serville, Melbourne Club: a social history, published Melbourne Club, 2017

The Borough and its People: Port Melbourne 1839 – 1939 by Margaret and Graham Bride is available for purchase from the Port Melbourne Historical and Preservation Society

3 Comments

Ken Miller

I am writing a book about my ancestors, the Dedes. They arrived in Sydney in 1839. James Graham was also a passenger on that ship. His writings are a major reference for me about the voyage. I have a transcribed copy of his fascinating journal if you are interested.

Phillip Bingley

James Graham is my Great Great Grandfather, I only found out a few years ago. Is there any other relatives I can talk too about this man?

David Thompson

Hello Phillip,

We are not aware of any current descendants of James Graham. Maybe another visitor to this page will know someone.