A Demographic Analysis of Liardet Street Port Melbourne Compared to Liardet Street, Liardet Grove and Liardet Terrace, London

by Ray Jelley

As the name suggests the objective of this study was to compare the occupations, and therefore indirectly, the social status of people living worlds apart, but with a common link; the names of the streets in which they lived. The methodology was an examination of the United Kingdom census documents from 1881, 1891 and 1901 for the streets in London that were named ‘Liardet’. The information obtained was compared to the information obtained from an examination of the Rate Book data available for Liardet Street, Port Melbourne in the same years as far as possible, but with not more than one year of difference.

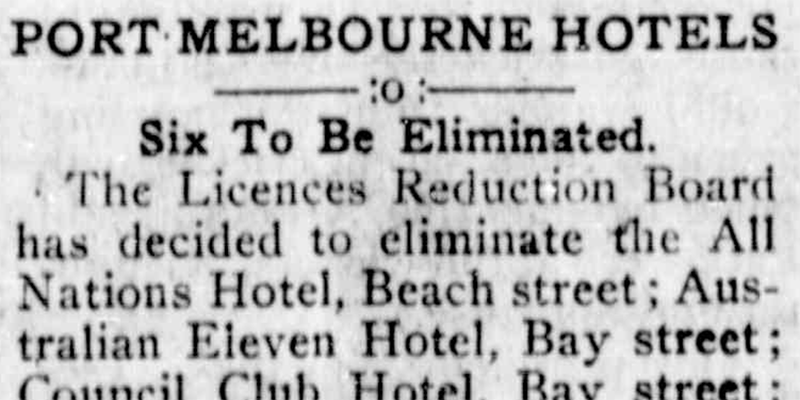

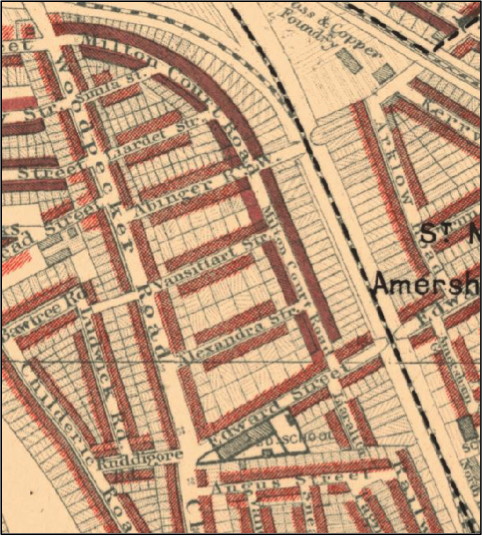

In 19th Century London in the Parliamentary Borough of Greenwich and the Civil Parish of St Paul, Deptford there were three streets that bore the name ‘Liardet’. These were: Liardet Street, Liardet Terrace and Liardet Grove. Geographically they were all close together, about 4.3km southeast of the Tower of London, south of the Thames and just south of where the South Eastern Railway branches into the London and Greenwich line and the South Eastern line. Liardet Street was the most northern and ran between Woodpecker and Milton Court Roads in a north-east, south-west alignment. Liardet Terrace was to the south of Liardet Street and was also known as Edward Street West (Figure 1). It was a continuation of Edward Street which ran from High Street, Deptford to the south-east ending at Woodpecker Road. Interestingly, the original name of Edward Street was ‘Loving Edwards Lane’ and High Street was known as ‘Bull Lane’ on Greenwood’s 1830 map of London.[1] In the 1881 census it was named as ‘Edward Street West/Liardet Terrace’. This was the only census that recorded the name Liardet Terrace and accordingly the only time that the data from the census was used in this analysis. Liardet Grove ran off the southern side of Liardet Terrace close to the South Eastern line railway, was a dead-end street and ran parallel to the railway line in a north-west, south-east alignment.[2] In modern day London only Liardet Street exists and now has two right angle bends where it used to be straight. However, it still runs between Woodpecker and Milton Court Roads. Liardet Terrace is now simply Edward Street, and Liardet Grove is a continuation of the old Pagnell Street following a major re-development of the area. In 1881, at the western end of Liardet Terrace, and on its southern side was the Clifton Road Board School. This school once sided onto the back of houses on the western side of Liardet Grove.[3] The school is still there but has been completely modernised and now covers a greater area than ever before. Houses in Liardet Grove were demolished to allow the many changes to the area. The present-day secondary school is named Deptford Green.[4]

All the houses in Liardet Street and Liardet Grove were constructed between 1871 and 1881 while the houses on the north side of Liardet Terrace pre-dated 1871. A map compiled between 1868 and 1873 shows that neither Liardet Street nor Grove existed when the map was prepared.[5] However, there were houses on the north side of Edward Street West/Liardet Terrace, although it was named Edward Street at that time (Figure 2). The 1881 census indicates that there were twenty-five houses in Liardet Street, fifteen in Liardet Terrace and thirteen in Liardet Grove.

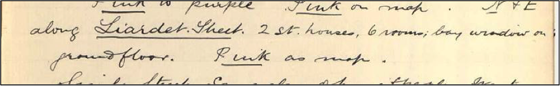

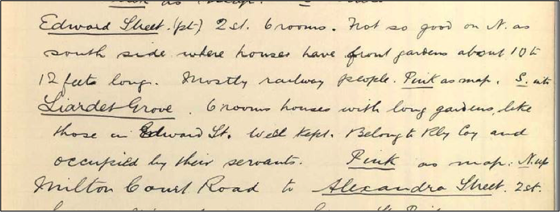

At the time of the 1881 census there were nine houses in Liardet street that were unoccupied, numbers 2, 3, 6, 17, 18, 21, 24, 26 and 28. This maybe an indication of how new they were. All the houses in Liardet Terrace and Liardet Grove were occupied. The 1891 census included the number of rooms in the houses occupied by each family if there were more than a single family living in the house. This shows that there was a total of six rooms in each house. This would have not changed over the thirty years for which this study is carried out. It was not until July 1899 that Charles Booth’s notebook records the area as it was inspected by Sergeant Vanstone of the London Constabulary. He noted that the houses in Liardet Street, Liardet Terrace and Liardet Grove were all of two-stories and comprised six rooms (Figures 3 & 4).[6]

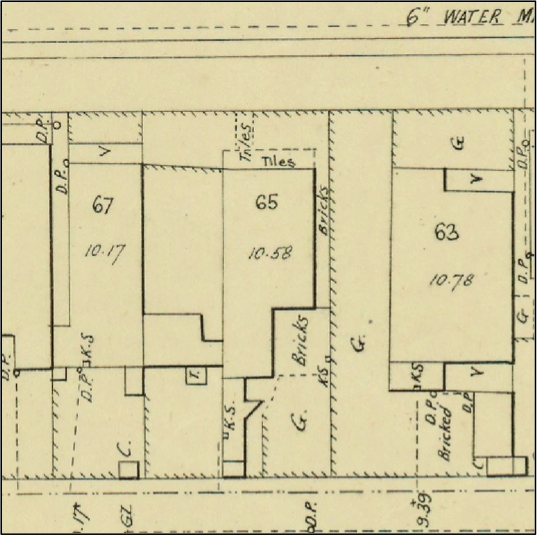

In contrast with London, the houses in Liardet Street, Port Melbourne were not all six room, double storied brick houses, but in 1880 were predominantly three or four roomed, single storied wooden cottages. The rate book indicates that there was a total of thirty-seven houses and twenty-nine of these were of wooden construction, six were constructed of brick and two were a combination of both, one having a wooden stable and a brick house. The number of rooms varied from two in the case of four houses to three for fourteen, thirteen with four rooms, three with five rooms, one with six and two with seven, although one of these was also a bakehouse and dwelling and another a shop and dwelling. The combination of dwelling and working premises was not obviously the case in London but may have been so for Marianne Bates and her daughter Mary who were described as having the occupations of ‘Needlework’ and ‘Dressmaker’ respectively, and who lived at number one Liardet Terrace. In addition, those who had the occupations of ‘General Servant’, ‘Housekeeper’ and ‘Nurse – Domestic’ most likely were engaged in work within the houses in which they lived. There were no shops as such, however. The only two-storied houses in Liardet Street, Port Melbourne in 1880 were the houses of John Adams, a marine surveyor at number 65 and that of Job Smith a baker with a bakehouse at 81 – this was on the corner of Liardet and Princes Streets, and still remains an impressive building. A two-storied house was built on the western side of John Adam’s house after 1901 as the Rate Books of 1891 and 1901 indicate that John Adam’s residence had ‘land’ as well. The 1895 MMBW plan shows that there was an open area on the west side of John Adam’s house (Figure 5).[7] John Adam’s house is now number 177 Liardet Street. As a strange quirk of fate Liardet Street, Port Melbourne runs along the southern boundary of Edwards Park, and Liardet Terrace, London is now Edward Street and was Liardet Terrace for only a short while.

A study of the census returns of 1881, 1891 and 1901 for Liardet Street, Terrace and Grove indicates that in many cases there was more than one worker registered at each address as well as the head of each family which was the data used in this study. The relevant age at which children joined the work force in one capacity or another appears to be between thirteen and fifteen, although the Factory Act 1878 did not allow children to work who were under ten years, and therefore children between ten and thirteen could have worked.[8] The 1881 census shows that children between the ages of six and thirteen were listed as ‘scholars’, but for the other two census collections their occupations were not designated at all. The age in Victoria at which children were able to work was tied to the Education Act of 1872 which stated that children from the age of six to fifteen were to attend school, although there were provisions for exemption.[9]In 1885 The Factories and Shop Act stated that:

No person under fifteen years of age shall be employed in any factory or workroom unless such person has been certified by an inspector of schools to have been educated up to the standard of education prescribed by “The Education Act 1872” … .

The London census returns show that in many cases two families occupied each dwelling, and where the family was small in number a boarder was also included as part of the household or a room was let to a single adult worker. In this case the worker was listed as ‘head’ although living alone. This suggests that a person categorised thus was quite independent of each of the other families who occupied the house. However, it is unlikely that all the occupants were isolated from each other in the one quite small, two-storied terrace house. A degree of cooperation would undoubtedly develop to maintain some sort of harmony. When these houses were built there was no provision for separate bathrooms and toilet facilities were in the back yard.

The same sort of analysis is not possible for the residents of Liardet Street, Port Melbourne as the Rate Books only recorded the head of the household and their occupational status. In the 1880 Rate Book all heads of household were working. However, in 1891 there were six individuals who were recorded with no occupation listed. In every case they were women and unfortunately, we can only surmise that they were supported by other members of the household who were possibly family and working or were boarders and paid an amount per week to cover household costs. Considering that the colony of Victoria was undergoing an economic collapse at the time as an aftermath of the land boom it was surprising not to find mention of ‘unemployed’ as an added descriptor, although the rate enumerator or head of the family may have been reluctant to add this descriptor. In 1901 the situation was the same with all heads listed as employed and six women having no occupation against their name. A similar state was probably the case – a member of the family was working, or the occupants were paying rent.

In Port Melbourne Liardet Street had outside toilet facilities as did London until at least 1897 when the MMBW began installing a sewerage system that would take wastewater from all premises in the area to the Werribee Treatment Farm. An extensive collection of plans is held by the State Library of Victoria which are available online. The very first Melbourne connection was in Port Melbourne on 17 August 1897 at the All England Eleven Hotel at the corner of Rouse and Princes Streets.[10]

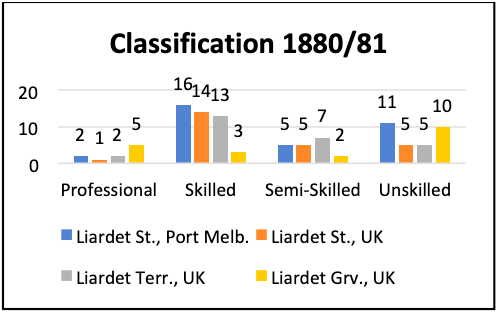

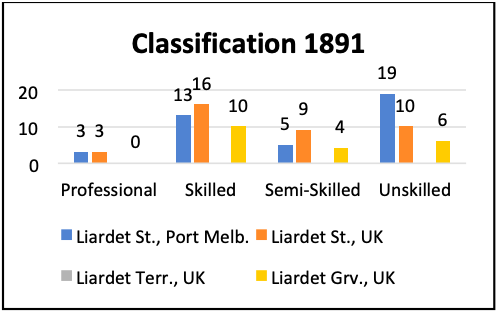

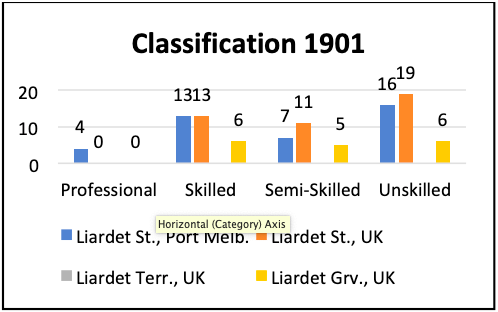

The occupations of the heads of households from the Rate Books of Port Melbourne and the census returns for the years 1880/81, 1891 and 1901 were analysed using an Excel spreadsheet and from this, the following bar charts were produced listing each location (Figures 6, 7 & 8). The individual occupations were graded into Professional, for those who were likely to have an extended level of study and educational qualifications beyond that necessary for those who were tradesmen. For example, schoolteacher, music engineer, master mariner, marine surveyor, or licensed victualler. Then Skilled for those who were likely to have been through a period of apprenticeship, education and assessment leading them to be artisans as defined by Eric Hobsbawn.[11] For example, engine driver, nurse, bricklayer, carpenter, or butcher. Following this was Semi-skilled for those such as railway porter, railway guard, iron moulder, carman, attendant, or shirt machinist. Finally, were those assessed as being unskilled, such as labourers, gas stokers, sawyer, or sheep skin dresser.

These charts enable some conclusions to be made:

1. There were very few Professional people living in these streets.

2. The numbers of Skilled people in Liardet Streets in Port Melbourne and London were quite similar and this included Liardet Terrace in 1881. The number of Skilled people in Liardet Grove was greatest in 1891 but was consistently less than Liardet Streets.

3. The number of Semi-skilled was consistent for Liardet Street, Port Melbourne and gradually increased for Liardet Street and Grove, London. Liardet Terrace was similar to both Liardet Streets in 1881.

4. The number of Unskilled people increased over time for both Liardet Streets and decreased modestly from 1881 to 1891 for Liardet Grove.

The overall conclusion was that the occupational demographics between Port Melbourne and London were similar and could be described as middle-class. Charles Booth’s legend establishes that all three locations in London were described with the colour ‘Pink’ and as ‘Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings’, and were certainly not classified as ‘working-class’, but more ‘lower middle-class’. The same could be said for Liardet Street, Port Melbourne in the same years.

Footnote

Since the publication of this article, Ray has received the following information from the Lewisham Historical Society regarding the naming of the Liardet streets in London.

Liardet Grove: Name approved 1877, now demolished. From John Evelyn Liardet a distant relation of Evelyn family who was their estate agent in Deptford until 1878.

Liardet Street (Woodpecker Road): Name approved 1877, now demolished. See Liardet Grove for details.

Liardet Terrace: Was in Edward Street, included in that road from 23 June 1882. For origin of name see Liardet Grove.

Thus the link to Liardet Street, Port Melbourne is unequivocally anchored in the Liardet family of Port Melbourne as John Evelyn Liardet (1829-1902) was the sixth child born to Wilbraham and Caroline. He returned to England and was instrumental in pursuing the Evelyn claim to the land on which the Naval Dockyards stood in Greenwich. At the time of the 1881 census he was living at 68 Breakspears Road, Deptford which was south of where Liardet Street, Terrace and Grove were located and in a more affluent area as the houses were coloured red where John lived (Middle class. Well-to-do) and yellow (Upper middle and upper classes. Wealthy) only a few houses away.

The 1881 census states that John’s occupation was ‘Engineer’ and his 21 year old son Leslie ‘Architect’. In the 1891 census his occupation was quoted as ‘Civil, Mechanical, Electric Engineer’. An all round talented man.

He and his wife Caroline had three of their children migrate to England with them: Leslie, Alice and Annie while Cavendish, their second son, stayed in New South Wales where all of their children were born. Three died when they were quite young. John went to England in the late 1840s because he married Caroline Sophia Orchard in St George’s Hanover Square in November 1850. He and Caroline came to Australia soon after because their first child Vernon was born in NSW in 1851.

Endnotes

[1] Map: Map of London Made from an Actual Survey in the Years 1824, 1825 and 1826 by C. and J. Greenwood

Source: Harvard Library, available from <iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/ids:8982548>

[2] Map: Charles Booth’s London

Source: London School of Economics, available from <booth.lse.ac.uk/map/14/-0.1174/51.5064/100/0>

[3] Ibid.

[4] Map: Google Maps Source: Google Maps, available from <www.google.com.au/maps/@51.4784522,-0.0364548,329m/data=!3m1!1e3>

[5] Map: Surrey III (includes: Bermondsey; Camberwell; London; Southwark; Stepney.), Surveyed: 1868 to 1873, Published: 1880

Source: National Library of Scotland, available from <maps.nls.uk/view/102347415>

[6] ‘George E. Arkell’s Notebook: Police District 44 [Peckham], District 45 [Deptford], District 46 [Greenwich],’ Charles Booth’s London, pp. 55 & 57; Note: The window that appears when selecting ‘Notebook Entry’ and Charles Booth’s map misidentifies Liardet Grove as Liander Grove. However, the census returns use the correct spelling.

[7] ‘Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works detail plan, 337, 338, 339, 355, 356, Port Melbourne [cartographic material],’ State Library of Victoria, available from <search.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/f/1cl35st/SLV_VOYAGER1177246>

[8] ‘Factory and Workshop Act 1878,’ Education in England, the history of our schools, available from <www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/acts/1878-factory-workshop-act.html>; ‘The Factory Acts,’ Technical Education Matters, available from <technicaleducationmatters.org/2016/02/16/the-factory-acts/>

[9] ‘The Education Act 1872,’ Victorian Historical Acts, available from <classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/tea1872134/>

[10] Robert D La Nauze, Engineer to Marvellous Melbourne (North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2011), p. 151.

[11] Eric Hobsbawn, ‘Artisan or Labour Aristocrat?’ The Economic History Review 37, No. 3 (August 1984): p. 359.

Figure 1: Map image of Liardet Street, Terrace (Edward Street) and Liardet Grove, courtesy of Charles Booth Poverty Map via the London School of Economics.

Figure 2: Map image of Deptford 1862-1873 courtesy of National Library of Scotland.

Figures 3 and 4: Extracts from Charles Booth Notebook for Deptford, courtesy of London School of Economics.

Figure 5: MMBW Plan Port Melbourne, 337, 338, 339, 355, 356 cropped, courtesy the State Library of Victoria.