Turville Place

by David F Radcliffe

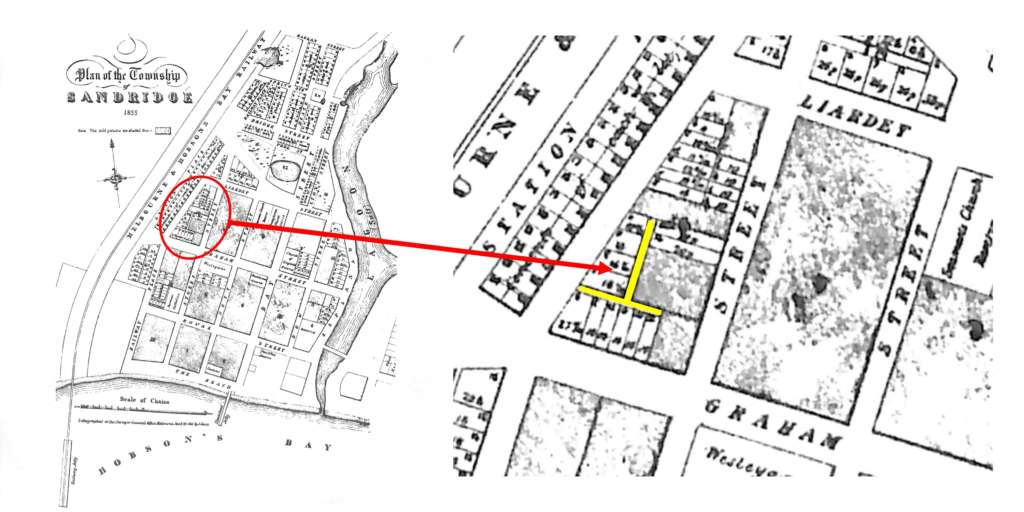

Because Princes Street, originally called Railway Place, runs parallel to the Melbourne to Hobson’s Bay Railway, the block bounded by Graham, Stokes, Liardet and Princes Streets (Crown Block 10) is trapezoidal rather than rectangular in shape. Turville Place was created to provide access to the interior parts of the southern portion of this block. Unlike “interior” streets in nearby blocks, for example, Florence Place and Barlow Street, the T-shaped Turville Place was laid out when the area was surveyed and subdivided in the early 1850s rather than as an afterthought. The name derives from the Turville family who had close associations with this right-of-way from the 1860s until the turn of the 20th century.

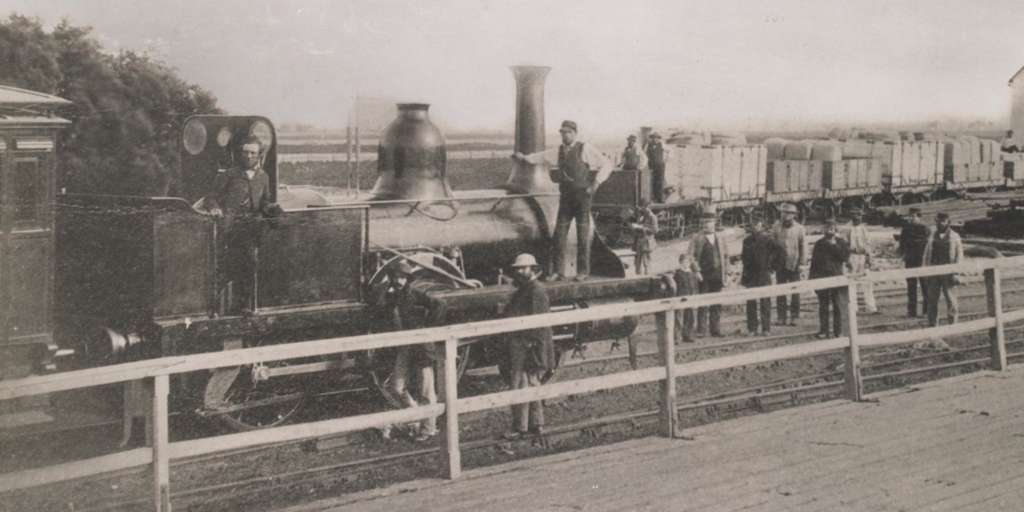

Thomas Turville married Ann Mackness in Leicester in 1846. Their first three children died young. The couple emigrated to Sydney in 1855 before moving to New Zealand seven months later. They relocated to Hobart where their son Frederick Mackness Turville was born in 1858. Next, they moved to Victoria settling in Sandridge where their daughter Ann Florence was born in 1860. Thomas Turville, an engineer by trade, was employed by the Melbourne and Hobsons Bay Railway Company.

In January 1869, a collision occurred near Flinders Street Station between a passenger train and one carrying ship’s ballast.[1] The Melbourne and Hobsons Bay Railway Company pursued Thomas Turville, the engine driver on the ballast train, and John Griffiths, the guard, for negligence but the outcome of the case is unclear. Some felt that the directors of the company should have taken responsibility.[2] However, this incident did not seem to impact Turville’s reputation locally as he narrowly missed out on gaining a seat on the Sandridge Borough Council in the 1872 elections.[3]

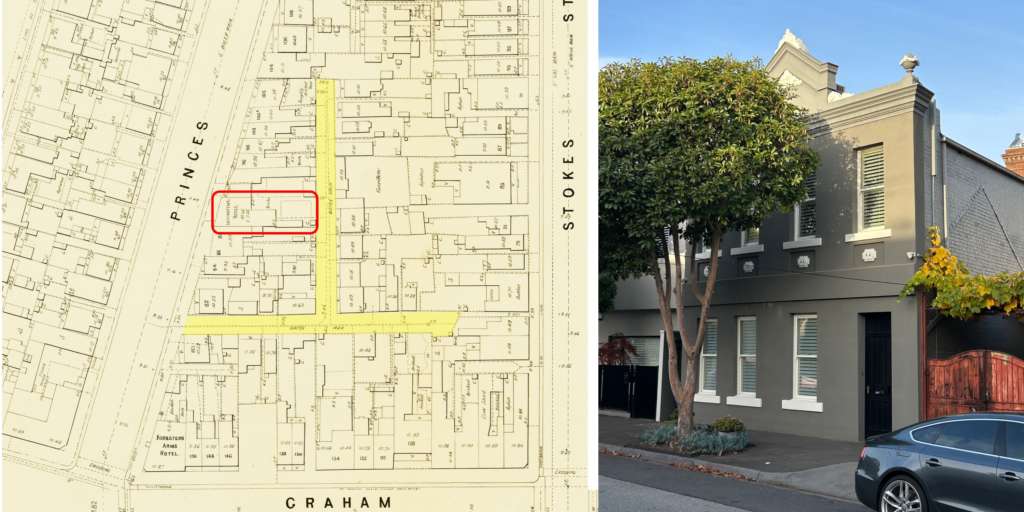

Initially, the family rented in Nott Street, but by 1863, Thomas Turville had purchased a substantial, two-storey brick home and shop in Railway Place. In July 1864 he applied for, and was granted, a licence to operate these premises as a hotel. As he noted in his application, the house contained “three sitting rooms and five bedrooms exclusive of those required for my family.”[4] The Turvilles operated the shop next to the hotel as a grocery business during the 1860s.

In the early 1870s, Thomas Turville had an engineering and brass foundry business based in Little Collins Street in the city, in partnership with Joseph Stead, a blacksmith, and fellow Leicesterian. For a time, Stead lived next door to the Locomotive Hotel. After his wife passed away, Joseph married Turville’s daughter, Ann Florence in 1879. Frederick Turville followed in his father’s footsteps becoming a brass founder, and was the senior partner in Turville, Dixon and Kemp, with premises on Queen Street, Melbourne.[5] The company was innovative, applying for several patents, receiving at least one.

Thomas Turville remained the publican at the Locomotive Hotel until 1885 when the licence was transferred to William Holyoak. Two years later Frederick Turville acquired the licence for the hotel. Subsequently, Frederick became the proprietor of the Prince Arthur Hotel opposite the Bowling Club on Nott Street. He was well-known and active in the community including being a Vice President at the Port Melbourne Football Club.[6]

The name Turville Place was adopted by the Port Melbourne Council in 1891.[7] Previously this right-of-way had been known locally as Connor’s Lane. John Connor, a stevedore, lived in the lane and acquired a string of properties there during the 1860s and 1870s. Thomas Turville also built up a property portfolio in the lane and on the adjacent part of Princes Street. The change of name was triggered by Mary Connor, John’s widow. Thomas Turville passed away in 1895.

After nearly 120 years ‘locked away’ in block 10, Turville Place was suddenly ‘opened-up’ to the neighbourhood in 1970. As part of the construction of the Graham Street overpass, the east-west portion of Turville Place off Princes Street was widened and extended through to Stokes Street. All but one of the buildings along Graham Street between Station Street and Stokes Street were demolished, and Turville Place was extended westward to Station Street. The portion of land remaining between Turville Place and the approach to the overpass became Turville Reserve. The image below indicates (in red) the many houses and business premises that made way for progress.

Delays caused by closing the gates at the Graham Street railway crossing had long been a source of local frustration. As early as 1954 there were calls to remove the crossing.[8] When it finally happened, one of the many buildings we lost was Forester’s Arms Hotel, which opened in 1866, on the corner of Princes and Graham Streets. As Pat Granger wryly observed, if it were not for the overpass, the Forster’s Arms may still have been in operation today.[9] The hotel can be seen in the centre of the postcard picture below.

The large ornamental rockery in the foreground of the postcard picture was at the intersection of Graham and Station Streets. The street lamp in the middle of the rockery is atop the Maskell and McNab Memorial erected to remember the engine driver, fireman and three passengers killed in the train crash at Windsor in 1887. This memorial was relocated to the Port Melbourne foreshore when the overpass was built. Perhaps not as postcard-worthy as the former rockery, nevertheless with its shrubs and greenery Turville Reserve provides a place to meet, a place to stop and reflect on our evolving neighbourhood.

If you spot a magpie in the Reserve, then you have connected with another side of Thomas Turville. In 1879, this ornithologically-minded engineer donated one English magpie and one blackbird to the Zoological and Acclimatisation Society of Victoria.[10] Noting that the English magpie is quite a different bird species to our local maggies, the question lingers, why did he only donate one bird and not a mating pair?

[1] ACCIDENT ON THE BRIGHTON RAILWAY. (1869, January 11). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.: 1848 – 1957), p. 6. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5816480

[2] No title (1869, February 9). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. 1854 – 1954), p. 2. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article177004480

[3] MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS. (1872, August 14). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic: 1848 – 1957), p. 3. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5836954

[4] Advertising (1864, July 13). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.: 1848 – 1957), p. 8. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5750645

[5] TURVILLE’S BRASS WORK. (1888, October 13). Standard (Port Melbourne, Vic.: 1884 – 1914), p. 3. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164932921

[6] FOOTBALL. (1889, April 13). Leader (Melbourne, Vic.: 1862 – 1918, 1935), p. 21. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198066852

[7] PORT MELBOURNE BOROUGH COUNCIL (1891, May 9). Standard (Port Melbourne, Vic: 1884 – 1914), p. 3. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164429771

[8] GRAHAM ST. RAIL CROSSING COMES UNDER FIRE (1954, August 28). Record (Emerald Hill, Vic.: 1881 – 1954), p. 2. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164510463

[9] Pat Granger (2017), Chartered Scoundrels: A Brief History of Port Melbourne Hotels (2nd Ed), pp. 50-51.

[10] TOWN NEWS. (1879, September 13). The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic: 1864 – 1946), p. 19. Retrieved May 29, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article143010642

2 Comments

Rebecca

How fascinating! Thanks for the comprehensive research and story.

David Radcliffe

Glad you found the story interesting