The Whitaker Family: Montague to Port

by David F Radcliffe

The Whitaker Family: Braidwood to Montague introduces Joseph Whitaker and Alice McFarlane who married in rural NSW in 1892. It tells the story of Alice being widowed aged 27 with four young children to support, the family’s move to Montague, an industrial area in South Melbourne, her second husband Ormas Towers deserting them and the impact on the family of the Great War and an unexpected pregnancy. The next phase of their lives, Montague to Port, is told below.

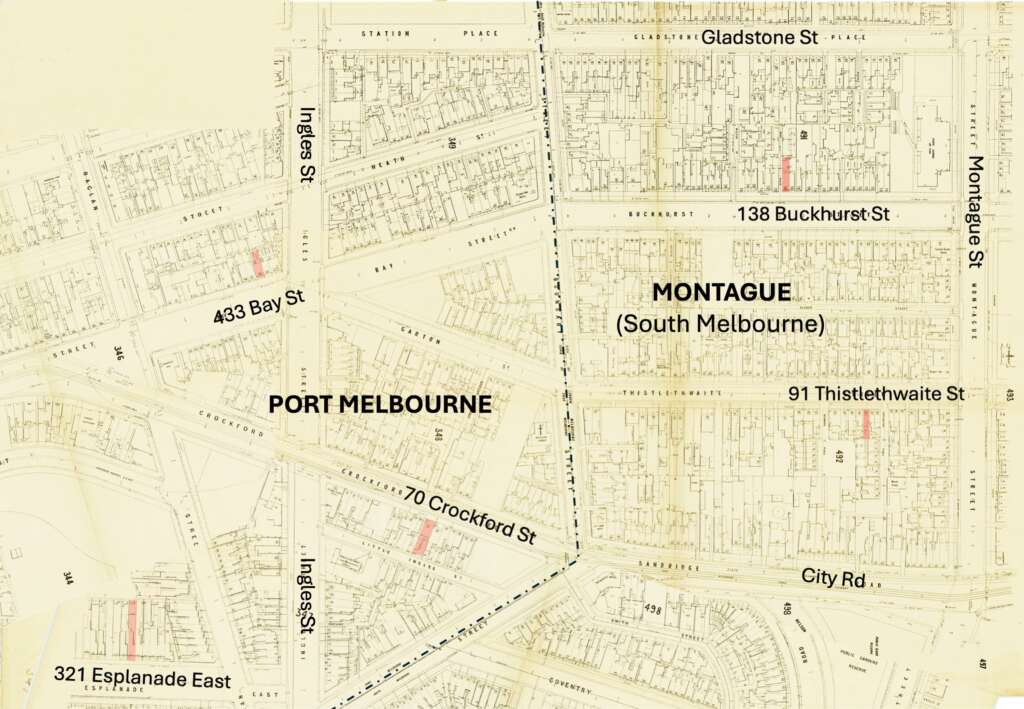

When Alice’s twenty-one-year-old daughter Emily gave birth to twins Alice and Jean at the Women’s Hospital in Carlton in January 1920, their father, Leslie Kennedy, was in the Kew Hospital for the Insane.[i] Emily and Leslie’s year-old marriage was on shaky ground. A few months after their first baby died in November 1918, Leslie found work at the McKay Harvester factory in Sunshine. The daily travel back and forth from Montague to the factory wore him down, so he suggested to Emily that they move to Sunshine. In April 1919, Leslie rented a room for them at the Sunshine Coffee Palace. However, Emily only stayed one night before returning to her mother’s place at 138 Buckhurst Street, Montague where her two older brothers, Allan (28) and Percy (26) and her younger half-brother, William Towers, aged 9 also lived.[ii]

In May 1919, Leslie lost his job at McKay Harvester. Next, he found work at Bannockburn (near Geelong). After contracting a bad case of influenza, Leslie spent ten days in the Geelong Hospital. He came back to live with Emily at Buckhurst Street but suffered a relapse with pleurisy and pneumonia. This impacted his mental health, and he was admitted to the Kew Hospital in early August 1919, suffering from ‘mania’. A year later, in July 1920, he was transferred to the Beechworth Asylum and discharged three weeks later.[iii] Leslie had had his first episode of ‘mania’ when he was 15 and he later spent time in another state institution during the 1940s, suffering from an unstated mental illness.[iv]

After Leslie was discharged from the Beechworth Asylum, he found work in the area and lived nearby with his mother. He wrote to Emily in Montague sending some money to support her and the twins. He claims that she wrote back saying that if he sent any more money, she would return it. Leslie wrote again offering to set up a home and asking her to come and live with him. She refused the offer, so he wrote again. Emily responded that she no longer wanted to live with him. This pattern repeated until January 1922 when Leslie came to Melbourne to talk with Emily. She told him she did not want to have anything to do with him and not to come near her or her mother Alice’s house again.[v]

In August 1923, Emily sued Leslie, now living with his sister in North Melbourne, for maintenance payments to support her and the twins. He was ordered to pay 12s 6d for each child.[vi] Leslie countered by suing for divorce on the grounds of desertion. Although the papers were served on Emily, she did not respond nor contest the case.[vii] The Decree Nisi became absolute in March 1924.

Notwithstanding a foot injury he suffered during the landing at Gallipoli in 1915, Emily’s brother Allan worked as a labourer and was very much part of street life in Montague. In November 1924, he was arrested for assaulting a police constable outside the Wayside Inn, corner of City Road and Ferrars Street. He was trying to stop them arresting his mate Herbert Stivey, who was accused of using ‘insulting words’. Allan was fined £5.[viii]

Two months later, in January 1925, Allan was arrested in a police raid on a two-up ‘school’ on a vacant allotment in Montague. Now described as an iron worker, he was one of forty-four men aged from 20 to 65 charged with unlawful gambling. Although playing two-up was an integral part of life for Australian soldiers like Allan during WWI, it was illegal here. The magistrate did not agree with the Act which described two-up players as “rogues and vagabonds” and he wished he could discharge all the defendants, but he had to uphold the law. The defendants were each fined £2 plus a further 5 shillings to cover the cost of the police car used in the raid and other expenses. Allan was singled out due to his 1924 conviction and fined £3.[ix]

Later in 1925, the whole family, Alice, Emily and the twins, Allan, Percy and William moved a few hundred yards from Montague to Port Melbourne, renting the double fronted, five-room weatherboard house at 70 Crockford Street. That December, William, aged 14, who worked at Laycock and Son on Normanby Road, registered as a cadet under the universal obligation for military training.[x]

In November 1926, three years after the maintenance order was issued before the divorce, Emily took Leslie to court for being £92 in arrears in his payments. He had been in and out of work due to a broken leg and broken finger and was earning £3 a week. Although the judge wondered aloud as to why Leslie was not given custody of the twins as an outcome of the divorce, he ordered the defendant to pay the arrears at 5 shillings a week in addition to the continuing maintenance payments.[xi] Emily returned to her pre-marital job as a textile machinist.

The national dock strike in 1928, a response to the punitive Waterside Workers’ Award, was short-lived.[xii] Nevertheless, the struggle continued with union members resisting the introduction of ‘volunteer’ labour to unload ships. Matters turned deadly on 2 November when police fired on unionists at Princes Pier. Some details in the following contemporaneous account are disputed.

As one shot rang out Allan Whittaker, 37 years, Crockford-street, Port Melbourne, who was among the men in the more advanced ranks, threw his arms into the air and fell backwards with a shout of “I’m shot.” Blood spurting from his face and neck confirmed his statement, and hundreds of men, shocked at the happening and knowing that certain death was whistling about them, suddenly became panic-stricken and a wild rearward rush was made. In the meantime, James Williams, 32 years, Station Street, Montague, had received a bullet in the right arm, and George Gray, 25 years, Dundas-place, Albert Park, had been struck in the left shoulder. When a fourth man fell bleeding from a leg wound the attackers as a whole realised that live cartridges were being used, and the utmost confusion prevailed in their ranks.[xiii]

Bleeding badly, Allan was taken by car to the Homeopathic Hospital (later Prince Henry’s) on St Kilda Road, South Melbourne.[xiv] His neck wound became infected, a result of the dreadful state of his teeth. It had to be drained periodically. In early January, Allan developed pneumonia, and later right-side empyema (pus build up in the pleural space) and paralysis of the right arm and leg. His empyema was drained under local anaesthetic in mid-January.[xv] Allan Whittaker (born Alan Prior Whitaker) died on 26 January 1929. Following a coronial inquiry, Allan Whittaker’s cause of death was recorded as “toxaemia and abscess of the brain resulting from a bullet wound to the face and neck; justifiable homicide”.[xvi]

A benefit concert was held in February to raise funds for Allan’s mother Alice. Tickets were 5 shillings and well-known local political activist Jenny Baines promoted the event in labour circles around Melbourne.[xvii] It is reported she also organised a protest at the Victorian Parliament in response to Allan’s death.[xviii]

Allan was laid to rest at the New Melbourne Cemetery (now Fawkner Memorial Park). The headstone also commemorated Allan’s brother, Cecil, who is buried in the Commonwealth War Grave at Lillers in France.

Although fifty-five-year-old Alice had now lost two of her sons, life for the Whitaker family went on. Her daughter Emily continued to work as a machinist until the mid-1930s while Percy and William were employed as labourers. In February 1936, Percy was arrested in Gladstone Street, Montague for playing ‘crown and anchor’, an illegal gambling game, and fined.[ixx] A decade earlier he was one of seven men arrested for playing another illegal game, this time in Lorimer Street, Port Melbourne.[xx] Like Allan and the two-up school in 1925, Percy and fellow returned servicemen who had played such games throughout the Great War did not think of them as being illegal.

During WWII, Alice’s youngest, William Towers, was mobilised and served on the home front.[xxi]

The trajectory of the Whitaker family changed in the post war years. In December 1949, Emily, now 50, married widower, George Sanderson, aged 56 in the vestry of the Presbyterian Church on Dorcas Street, South Melbourne. William was one of the witnesses.[xxii] George, who was born in Leith, Scotland, emigrated to Western Australia in 1911 where he found work as a dairyman. He enlisted in the AIF in 1916, was wounded in action in France and returned to farming in WA. His wife Beatrice, whom George had married prior to enlisting, died in April 1942.[xxiii] Subsequently, George moved to Victoria, possibly as late as 1949. He was living with the Whitaker family at the Crockford Street house when the pair married suggesting he may have boarded with them.

In July 1950, Emily bought the four room Victorian cottage at 321 Esplanade East, Port Melbourne.[xxiv] For a family who had always been renters, moving frequently from place to place in the 1910s and ‘20s, this purchase represented a significant change in their fortunes. How Emily managed to accumulate the funds to purchase the house is unclear, although it is worth noting that George inherited £1058 from his first wife’s estate.[xxv] Emily, George and Alice moved to 321 Esplanade East around 1955. In the interim they retained the sitting tenant.[xxvi] By now the Housing Commission had served a notice on the owner of 70 Crockford Street under the Slum Reclamation and Housing Act of 1938.[xxvii] Growing up in this area in the 1940s and ‘50s, Kay Rowan remembers the Crockford Street house being somewhat ramshackle with an overgrown vine on its drooping front veranda awning.[xxviii]

In March 1957, Alice’s son William married Hazel Maria (Alma) Harris at Holy Trinity Church in Bay Street, Port Melbourne. Now aged 44, he was a forklift driver while Alma, aged 40, was a textile machinist. Both were living at 433 Bay Street, near Raglan Street.

Two months later the family matriarch, Alice (Whitaker) Towers passed away at the Esplanade East house aged 84. She had suffered heart disease for several years. Sadly, she was also in a state of cognitive decline.[ixxx] Alice was laid to rest at Fawkner Memorial Park alongside her son Allan.

Percy Whitaker never married. For a time he lived in Glover Street South Melbourne and later in Alfred Street, Montague.[xxx] When the ANZAC Commemorative Medallion was created in 1967 to honour those who participated in the Gallipoli Campaign, Percy applied for one as Allan’s next of kin.[xxxi] When Percy passed away in November 1972, aged 77, he was living with his sister Emily at the Esplanade East house. Her husband, George had died five years earlier.

Emily passed away in 1973.[xxxii] Her estate was valued at £8,536 of which £7,300 was the Esplanade East property. In her Will, Emily directed her estate be used to support her twins, Alice and Jean, now both 53 and if they died before her then the money was to go to George’s niece in Scotland.

Neither Alice nor Jean married. At the time of their deaths, they resided at Devon Lodge at Woodend in the Macedon Ranges. Once a popular guest house and tea rooms, Devon Lodge became a Special Accommodation House for the Health Commission of Victoria in 1969.[xxxiii] Alice suffered from schizophrenia and died of a stroke in July 1978 while Jean died in December 1986.[xxxiv] Their death certificates list George Sanderson as their father. Is possible he adopted them after marrying Emily?

Alice’s youngest, William, passed away in 1995 and his wife Alma two years later. As they did not have any children, there were now no descendants of Alice to carry the family story forward. Any family photographs are gone and there are no pictures of her boys in uniform. There is no family remaining to place flowers on the grave she shared with her slain son, Allan.

But for the shooting of Allan Whittaker at Princes Pier, the story of his family would likely never have been told. While every family story is unique, many of the vicissitudes visited on Alice McFarlane / Whitaker / Towers and her children were experienced by other working families in and around Montague and Port Melbourne during the first half of the 20thcentury.

[i] Opened in 1871 as the Kew Insane Asylum, between 1905 and 1934 it was called the Kew Hospital for the Insane. https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/VA2840.

[ii] Kennedy v. Kennedy, VPRS 283/P0002, 1923/314, PROV.

[iii] VPRS 7680/P0001, Register of Patients, Kew Hospital for the Insane 1913-10-20 to 1919-08-18, PROV.

[iv] NAA: B2455, KENNEDY LESLIE JOHN. Letter from RSSAILA in 1947.

[v] Testimony of Leslie Kennedy in Kennedy v. Kennedy, VPRS 283/P0002, 1923/314, PROV

[vi] 1923 ‘Maintenance Security Estreated.’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), 17 August, p. 12. , viewed 07 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article203627485

[vii] 1923 ‘DIVORCE COURT.’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 1 December, p. 14. , viewed 07 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1982501 and Kennedy v. Kennedy, VPRS 283/P0002, 1923/314, PROV

[VIII] 1924 ‘At Montague.’, Record (Emerald Hill, Vic. : 1881 – 1954), 6 December, p. 2. , viewed 06 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164447492

[ix] 1925 ‘SEQUEL TO TWO-UP RAID.’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), 17 January, p. 15. , viewed 06 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155555381

[x] NAA: CT190/9, 3/186

[xi] 1926 ‘Children’s Maintenance.’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), 13 November, p. 17. , viewed 07 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202203581

[xii] 1928 ‘WHARF STRIKE ENDS’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 17 September, p. 7. , viewed 08 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3957308

[xiii] 1928 ‘RIOT AT PORT MELBOURNE’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), 3 November, p. 21. , viewed 04 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204255347

[xiv] Allan Whitaker died on 26 January 1929.

[xv] Medical report as part of the Coroner’s Inquiry into the death of Allan Whittaker, 28 March and 11 April 1929. PROV: VPRS 24/P0000, 1929/428.

[xvi] Alan Prior Whitaker, Death Certificate, BDM Victoria 6043/1929.

[xvii] 1929 ‘A.L.P. NOTES.’, Labor Call (Melbourne, Vic. : 1906 – 1953), 28 February, p. 10. , viewed 04 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article249960384

[xviii] 1931 ‘TRADES HALL COUNCIL’, Labor Call (Melbourne, Vic. : 1906 – 1953), 11 June, p. 12. , viewed 04 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article249980305

[ixx] 1936 ‘GAME PLAYED AT WAR’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 18 February, p. 9. , viewed 08 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11883331

[xx] 1927 ‘SOUTH MELBOURNE COURT’, Record (Emerald Hill, Vic. : 1881 – 1954), 2 April, p. 8. , viewed 07 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164453285

[xxi] NAA: B883, VX106750.

[xxii] Marriage Certificate, George Sanderson and Emily Whitaker, 27138/1949 BDM Vic.

[xxiii] 1942 ‘Family Notices’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 30 April, p. 1. , viewed 08 Apr 2025, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article47330491

[xiv] Certificate of Title, Part of Crown Allotment 8, Section 47a, Parish of South Melbourne, Vol 1613 Folio 403.

[xxv] Beatrice Annie Sanderson, Probate Jurisdiction, 532/1942.

[xxvi] Ray Jelley, 321 Imagined Settlement, TEL Publishing, 2018, Chapter 8.

[xxvii] Certificate of Title, Part of Crown Allotment 3 Section 45, City of Port Melbourne, Vol 3083 Folio 576.

[xxviii] Kay Rowan, Personal Communication, March 2025.

[ixxx] Alice Tower’s death certificate uses the term ‘senile’.

[xxx] Federal Electoral Rolls

[xxxi] NAA: B2455, WHITTAKER ALLAN.

[xxxii] George and Emily’s ashes were interned together at the Altona Memorial Park.

[xxxiii] Trevor Budge & Associates, Macedon Ranges Cultural Heritage and Landscape Study, Vol 4, Part 2, June 1994, pp. 374-376.

[xiv] Alice Kennedy’s ashes were interned with Emily and George while Jean, the last family member to pass, was cremated at the Ballarat Cemetery.

1 Comments

Albert Caton

[This is a comment irrelevant to the main theme of this story; furthermore, it is so long since I used a Melbourne suburban train that what I describe might continue to this day, and so be meaningless.]

The aerial photograph of Montague shows an interesting feature apparent on the railway station. The rear of the platform across the railway line shows a ‘wall’ of advertising, a feature common to most suburban platforms at the time. The billboards were made of sheets of tin attached to a wooden frame, the structure about 2~3 metres high and extending along much of the platforms’s length. Each advertising poster, changed perhaps each couple of months, was assembled from colour-printed paper sheets glued to the tin backing, the advertisement overall extending for about 3~4 metres. The images had a captive audience of commuters.

Subjects varied widely. I remember one advertising the visit, to one of the city theatres, of ‘Luisillo and his Spanish dancers’. Another advertised the movie ‘Tea and Sympathy’ (“Years later, when you talk of this—and you will—please be kind”). And I was encouraged to use Saunders Malt Extract by a bonny blond-haired baby holding onto a crane hook with one hand, the other holding a steel girder.