The Whitaker Family: Braidwood to Montague

by David F Radcliffe

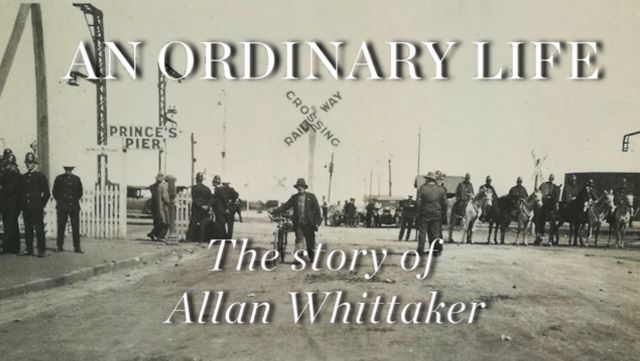

Allan Whittaker, a stevedore, was shot by police at Hogans Flat, near Princes Pier, on 2 November 1928. The injuries he sustained resulted in his untimely death on 26 January 1929. He was 38. These events have been commemorated annually since 2013. A short film, An Ordinary Life: The Story of Allan Whittaker, released in 2025, provides a snapshot of Allan’s life and the circumstances leading up to his death.

This article aims to complement the Allan Whittaker film by expanding on his family background: the story of his parents and the lives of his four siblings. It explores his family’s origins in rural NSW in the 19th century and the transition to urban life in industrial Montague, South Melbourne, during World War One. They endured many hardships and multiple tragedies.

Allan Whittaker’s name is a source of some confusion. He always spelt Whittaker with a double ‘t’ even though all his immediate and extended family spelt theirs Whitaker (single ‘t’). Similarly, he always referred to himself as Allan (double ‘l’), although his mother knew him as Alan Prior Whitaker.[1]

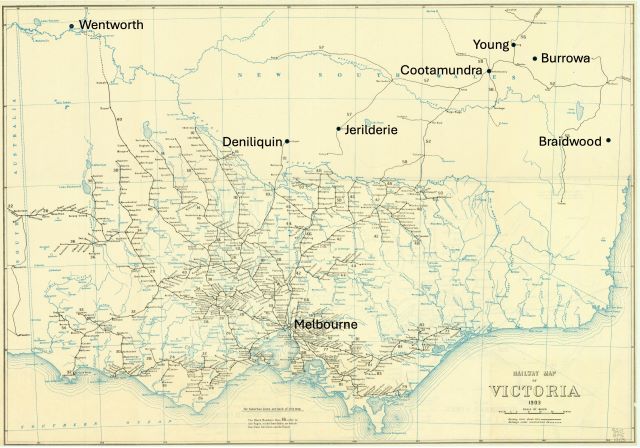

Allan’s grandfather and father were watchmakers. Born in Nottingham, England, John Whitaker (Allan’s grandfather) was convicted of housebreaking in 1835 and transported to Sydney for life. Assigned to work on a pastoral station at Braidwood on the Southern Highlands of NSW, 280 km southwest of Sydney, he was granted a ticket of leave in 1844. This enabled him to become self-employed and acquire property subject to certain restrictions. Soon after gaining this degree of freedom, thirty-six-year-old John married sixteen-year-old Zillah O’Brien. She was the daughter of two convicts, Thomas O’Brien and Maria Roberts, born in the Female Factory in Sydney.[2]

John and Zillah Whitaker had twelve children. Their seventh child, Joseph, born in Braidwood in 1861, was Allan’s father.[3] In 1875, now in his late sixties, John Whitaker opened a watch and jewellery shop in Burrowa (now Boorowa).[4] Joseph took over the shop in 1891 when John retired, but it closed soon after, coinciding with a dramatic population decline in the early 1890s of this former gold mining boom town.[5]

Allan’s parents, Joseph Whitaker and Alice Euphemia McFarlane, married in Young, NSW in 1892.[6] Joseph was 29, and Alice was 19. She was born in Jerilderie, where her father was a bootmaker. Alice gave birth to Alan Prior Whitaker in Cootamundra in October 1892. They moved to the region around Jerilderie and Deniliquin, where Joseph operated a small business as a watchmaker and jeweller, specialising in gilding and electroplating. Given the banking crisis of 1893 and the economic depression, trading conditions were difficult. During this time, Alice had five more children. Percy (1894), Cecil Darker (1896), Alfred (1897), and Bertie (1898) were all born in Jerilderie, although Alfred and Bertie lived for less than a year. Their daughter, Emily, was born in Deniliquin in 1899.

Joseph Whitaker passed away unexpectedly of acute meningitis in January 1900, aged 38. Twenty-seven-year-old Alice was left with four young children to support: Allan (aged 8), Percy (aged 6), Cecil Darker (aged 3) and baby Emily.[7] The people of Deniliquin raised a subscription to support the immediate needs of the destitute Alice and her children. In March, the town held a charity concert to raise further funds.[8] Alice also received some support from a statewide charity. Here, the story goes cold. There is no record of where they lived or how Alice made ends meet. One of the consequences of Joseph Whitaker’s premature death was that neither Allan nor his brothers had the opportunity to learn the family trade of watchmaking.

In 1910, Alice, now 37, married twenty-five-year-old Ormas Mcquarrie Towers in Wentworth, near Mildura, on the NSW side of the border where the Darling meets the Murray. Her three boys were of working age: Allan (18), Percy (16), and Cecil (14). Emily was eleven. Alice and Ormas had one child, a son, William Ormas Towers, born in April 1911. A year or so later, their blended family, all except Allan, relocated to South Melbourne, renting a house on Moray Street.[9] This move may have been triggered by the failing health of Ormas’s father, William, his father’s admission to Yarra Bend Asylum in April 1912, and his death that August or the death of his mother, Bridget, the following year. [10] By 1914, Alice, Ormas and the family had moved around the corner, renting a house on Dorcas Street. Then, World War I intervened.

Alice’s three older sons joined the AIF and fought in “the war to end all wars”. Allan was living in Sydney and working as a waiter in a club when he enlisted in August 1914, just a month after war was declared. There are several curious things about his enlistment form. He states his place of birth as Yarraville rather than Jerilderie. He gives the address of his next-of-kin, his mother, Alice, as 45 River Street, Yarraville. There is no record of a house at this address nor of Alice ever living in Yarraville. Further, Allan states he was a member of the East Surrey Regiment for a year. Given the circumstances of his life, this claim seems highly improbable.[11]

Allan was wounded in Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, injured by shrapnel in the left foot. He was listed in the Herald on 17 May amongst the wounded from NSW, but the telegram sent the same day to inform his mother Alice was probably not received as it went to River Street, Yarraville.[12] Allan spent time in the general hospital in Heliopolis, Egypt, before being shipped back to Australia on the HMAT Hororata, arriving in Port Melbourne in August 1915. Allan went on to Sydney. We do not know if he saw his mother while the ship was in port. He was discharged from the AIF in January 1916. Allan remained in Sydney, receiving a modest pension of £3 per fortnight, reduced to £1.10s in March 1917.[13]

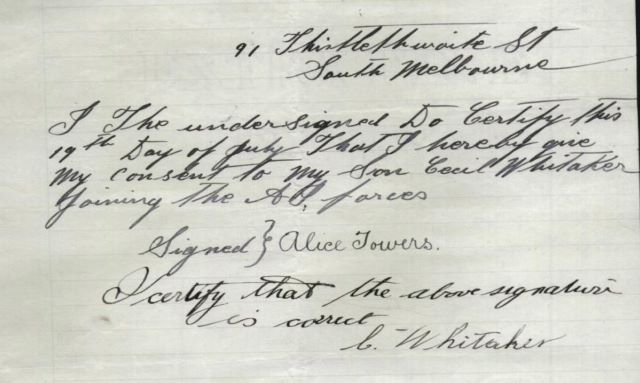

Meanwhile, Allan’s brothers had enlisted: Percy in June 1915 and Cecil the following month. Percy worked as a railway porter, and Cecil was a motor driver. The family was now living at 91 Thistlethwaite Street in the Montague neighbourhood of South Melbourne. As Cecil was only 19, he needed a letter of consent from his mother (see below).

Percy Whitaker embarked from Port Melbourne on the HMAT Anchises in August 1915, expecting to see action in Gallipoli. Instead, he spent nine months in Egypt after the Allies began evacuating troops from this failed campaign that October. Percy was transferred to England in mid-1916 before being deployed to France in March 1917. Cecil embarked in October 1915, travelling via Egypt to England. He saw service as an artillery gunner in Belgium and France. Both spent periods at the front interspersed with furloughs back in England. Like many Australian soldiers in WW1, Cecil and Percy were disciplined on several occasions, usually for being absent without leave; they weren’t angels. Cecil’s file indicates he was Court-Marshalled in March 1917. However, the details are not included.[14]

Back in Montague, Alice battled several domestic issues. In May 1917, her husband, Ormas, moved to Port Albert to work in a sawmill. He was using the alias Tom Cahill and is reported to have moved in with another woman. That August, Alice, described as a “cheerful looking middle-aged lady”, took him to court to seek maintenance payments for their six-year-old son William. She was awarded 15 s a week.[15] Her address is listed as 552 City Road, South Melbourne.[16] A year later, she was living at 138 Buckhurst Street. So, although Alice moved frequently, she remained in Montague. With Allan in Sydney and Percy and Cecil serving in Europe, Alice depended heavily on her daughter Emily, who brought in a steady wage working as a textile machinist.

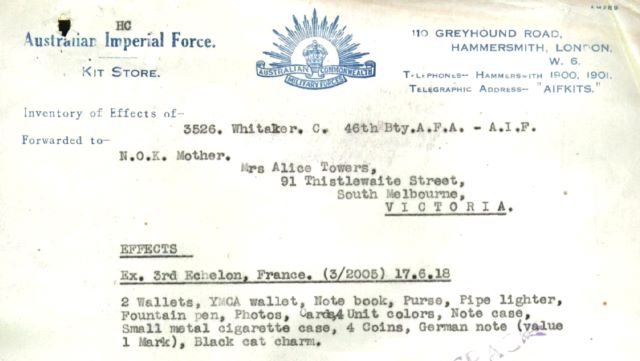

For Alice, anxiety about news from Europe was ever-present. Percy was wounded on at least two occasions, the second being in April 1918. But her worst fears were realised a few weeks later when Cecil was killed in action in France on 29 April 1918. As his next of kin, Alice received a small parcel with Cecil’s personal effects: several wallets, a fountain pen, a notebook, a cigarette case, a pipe lighter, photos, cards, Unit colours, a German banknote and his black cat charm. Although the parcel had an out-of-date address, given the community of Montague, doubtless, the postie found Alice and delivered these few possessions Cecil left behind.

Compounding matters for Alice, her nineteen-year-old breadwinner, Emily, was now pregnant. The father was Leslie Kennedy, a twenty-six-year-old iron worker who boarded with the family, helping to pay the rent. Before coming to Melbourne, Leslie had enlisted in the AIF in September 1915 but was discharged as medically unfit.[17] Emily and Leslie were married at St Luke’s Church of England in South Melbourne on 14 September 1918, with Alice as a witness. Emily gave birth to their son two weeks later. She named him Cecil Darker Kennedy after her recently deceased brother.[18] Sadly, the baby only lived for nine weeks.[19] Emily and Leslie continued to reside at Buckhurst Street.

By then, Percy had returned from war service and resumed his previous job as a railway porter. Allan had moved down to Melbourne, was employed as a ship’s steward, and lived with the family in Buckhurst Street. Alice’s estranged husband, Ormas, rented nearby on City Road and worked as a grip man on the cable trams. As well as adjusting to post-war life, the community were dealing with multiple waves of the ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic. Trouble was brewing for Emily and Leslie. For Alice (Whitaker) Towers, now in her mid-forties, still mourning the loss of her son Cecil, the coming decade would test her just as the previous two had done.

The Whitaker family’s turbulent start to the 1920s, Allan’s tragic death and the latter years of Alice and Emily in Port Melbourne are recounted in The Whitaker Family: Montague to Port.

[1] Alan Prior Whitaker, Death Certificate 6043/1929 BDM Vic. There is no record to confirm his given name when born. The name in his death certificate, Alan Prior Whitaker, was provided his mother. His brother Percy only became aware of Allan’s second name, Prior, during the inquest into Allan’s death.

[2] The amazing story of Maria Roberts and how her daughter Zillah came to marry John Whitaker is told in The transformative power of family history literature: ‘reckoning with the past’ through biography, fiction and memoir, Master of Applied Arts & Humanities (Research) Thesis by Corinne Vale, University of Canberra, https://doi.org/10.26191/s2f1-8y02 Accessed 11 March 2025.

[3] There is no record of his birth, so the year is estimated from Joseph Whitaker, Death Certificate BDM NSW 1345/1900.

[4] ‘Advertising’, The Burrowa News (NSW) 11 December 1875, p. 1. Web. 11 Mar 2025 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103373509.

[5] ‘Advertising’, The Burrowa News (NSW) 1 May 1891, p. 3. Web. 11 Mar 2025 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article101425082. John Whitaker died in August 1892.

[6] There is no record of the marriage, so the year is estimated from Joseph Whitaker, Death Certificate BDM NSW 1345/1900.

[7] Death Certificate, Joseph Whitaker BDM NSW 1345/1900. Curiously, Allan’s name is spelt with the double “l’ in the certificate.

[8] ‘Advertising’, The Pastoral Times (South Deniliquin, NSW) 3 March 1900, p. 2. Web. 11 Mar 2025 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article278849872.

[9] Electoral Rolls, 1913 and 1914.

[10] ‘Family Notices’, The Age (Melbourne) 21 August 1913, p. 1. Web. 12 Mar 2025 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197490884.

[11] NAA: B2455, WHITTAKER ALLAN

[12] ‘SECOND MILITARY DISTRICT’, The Herald (Melbourne) 15 May 1915, p. 1. Web. 12 Mar 2025 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article242352440.

[13] NAA: B2455, WHITTAKER ALLAN and NAA: B73, R44423

[14] NAA: B2455, WHITAKER CECIL

[15] ‘ANOTHER LADY’, Record (Emerald Hill)18 August 1917, p. 3. Web. 12 Mar 2025 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75014145.

[16] The 1917 electoral roll indicates Alice lived at 352 City Road, not 552 as reported in the press. When Leslie John Kennedy re-enlisted in February 1918, he gave his address as 552 City Road.

[17] When Leslie John Kennedy enlisted in September 1915, he was living with his parents at Beechworth. He was discharged as medically unfit since one leg was shorter than the other due to a fracture he suffered as a boy growing up in Beechworth. NAA: B2455, KENNEDY LESLIE JOHN.

[18] Darker was the family name of John Whitaker’s mother. One of Joseph’s brothers was named John Darker Whitaker.

[19] Cecil Kennedy died of bronchial catarrh on 30 November 1918 at the Children’s Hospital.