A Modern Woman from Garden City

by Robyn Watters

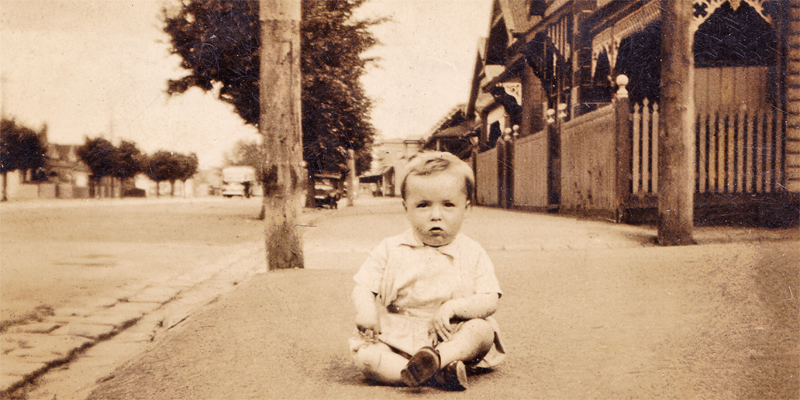

Norma Madeline Watters

Born: 7 June 1924, Albert Park (at home)

Died: 23 April 2021, Brighton

We often imagine that women born a century ago saw their destiny only as wives and mothers fleshed out only by the necessity to bring in money if they were from the working class. My aunt Norma Madeline Watters born in 1924 went down a different path that I think had more in common with today’s women than those of yesteryear.

My aunt walked out of her Garden City home every working day of her life to catch public transport into town and into the office. 400 Williamstown Road (formerly numbered 124) on the corner of Beacon Road was ideally sited with the bus stop at the side entrance of her family’s property.

Norma’s trajectory into the office was a huge step up from her mother’s pre-marriage work as a cigarette machinist. Her mother Ellen, growing up in notorious Little Lon, attended the Model School perhaps leaving before the legal age. Norma benefitted from this as Ellen knew about and ensured that her daughter went to the Model School’s ultimate successor, the prestigious Mac.Robertson Girls’ High School.

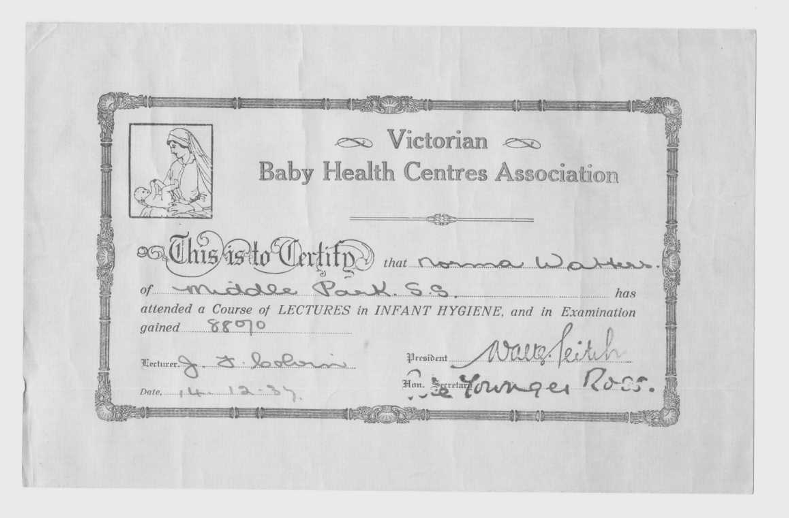

Norma excelled at English, shorthand, typing, mothercraft nursing and cooking at Middle Park Central School and Mac.Rob. The achievement at the latter two subjects always bemused her and she regaled others with the story that her only mistake in the final mothercraft nursing exam was that she forgot to put the matinee jacket on the dummy baby. Her rationale for excelling at cooking was that the teacher confused her with her elder sister Patsy who had been a former dux of the cooking class and simply kept on handing out the prize to a Watters. Norma completed Intermediate (Year 10) and was not disappointed to matriculate as she said “everyone” was leaving school by then anyway.

No modern gap year for Norma, her employment records indicate that she took no time off between completing the 1939 school year and starting work at the Myer Emporium Ltd. on 8 December in the General Office. She was a typiste and calculator operator. To further her employability, she immediately and prior to Christmas, started night school at the largest business school of the day, Zercho’s.

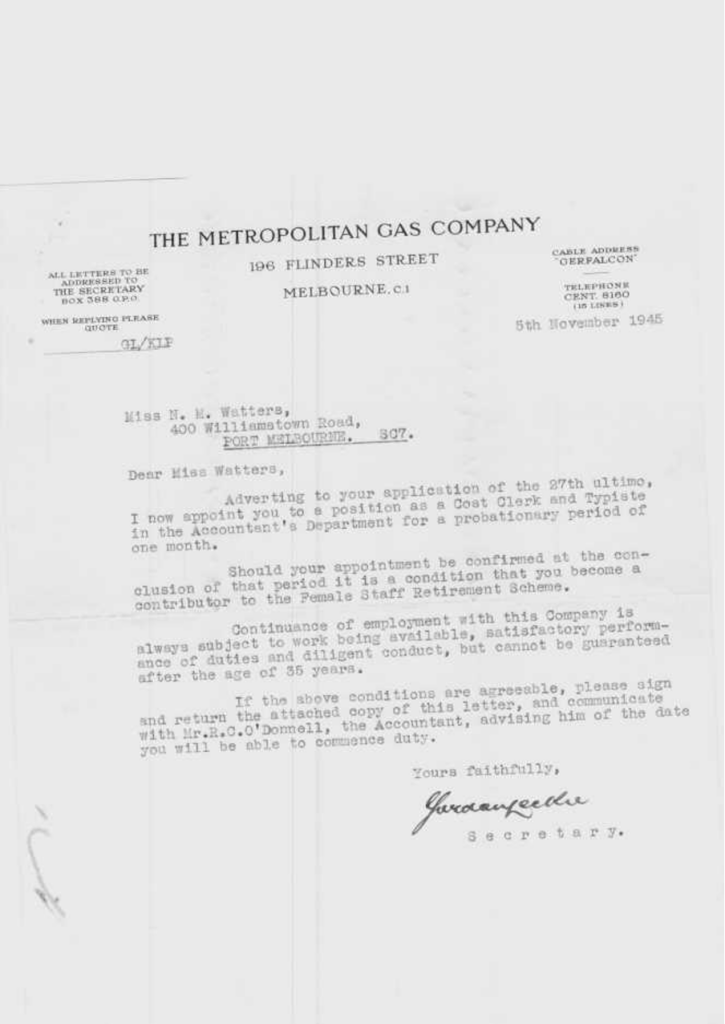

The general insecurity of work and relatively poor working conditions are highlighted in a letter of engagement that an employer of Norma’s gave her in 1945. The Metropolitan Gas Company warned that “Continuance of employment ….. cannot be guaranteed after the age of 35 years.” I asked Norma whether at the time she thought this was a bit rich. She said “we thought so”. Perhaps the gas company were confident that they couldn’t be prosecuted for discriminatory work practices and that there would be a steady supply of returned service men to fill the vacancies.

Norma worked in a variety of jobs over the years; she shone at stenography and was often lauded at Melbourne’s Pitman House as a star ‘recruit’ when she visited at lunchtime from her current employment. Her ability to take lightning fast and accurate shorthand stood her in good stead throughout her working life. She was able to move jobs when and if she pleased with this passport to employment. Fortunately for her, she also coped with the introduction of the Dictaphone as she was an excellent typiste. She told me she didn’t want to learn about computers when they entered the office as that meant she may have had to help someone else!

Norma never did marry.

“I have come to tell you a terrible fact. Only one out of every ten of you girls can ever hope to marry. This is not a guess of mine. It is a statistical fact. Nearly all the men who might have married you have been killed. You will have to make your own way in the world as best you can. The war has made more openings for women than there were before. But there will still be a lot of prejudice. You will have to fight. You will have to struggle.” 1917 Senior Mistress of Bournemouth High School for Girls to the assembled sixth form girls. (‘Singled Out’ by Virginia Nicholson, Penguin Books 2008 at page 25)

Whilst this Senior Mistress spoke to girls during World War One, I’d be fairly confident that my aunts were given a similar talk by their headmistress or by family during World War Two. Their chances of marriage whilst not so low as Australian women during World War One, still left them with fewer options. They had to face the fact that their life trajectory would be skewed in one direction – towards the workplace.

Norma though did enjoy being a ‘modern women’ in the best sense she could at the time. She had her own pay packet, albeit less than a man doing the same job, and she treated herself to massages at the City Baths, films and of course makeup (“Lizzie Arden”) and clothes. Norma remained an avid fan of Myer throughout her life supporting them by spending considerable sums of money there.

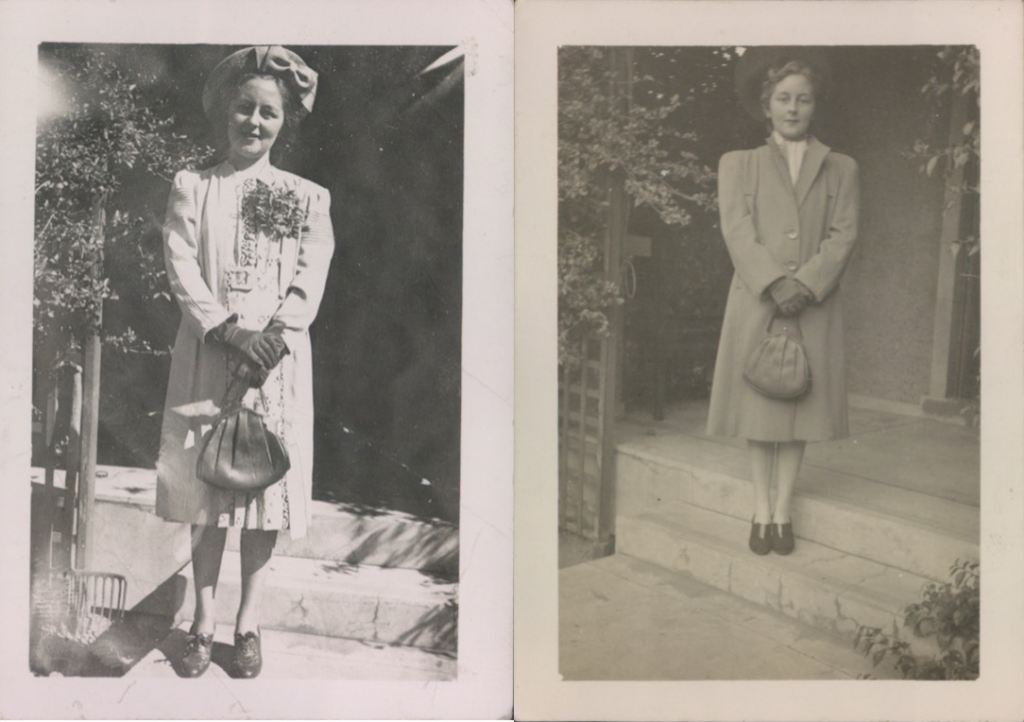

Like many young women, Norma had a studio portrait taken and “paid a lot of money to look that good”. The brooch apparently is a copy of what the young Queen Elizabeth II, of a similar age to Norma, wore.

When meeting new people that she was keen to impress, she and a girlfriend had their story worked out that they hailed from Carnegie! Neither had been to Carnegie but were acutely aware in those days that it sounded better than coming from Port Melbourne.

Did Norma miss out by not marrying and having children? I think not and so did Norma. It would certainly not have suited her personality to be dependent upon a man particularly one with a working-class wage at a time when family planning was rudimentary. A house with screaming children would have driven her up the wall. Indeed, Norma had much to gain by doing things her way outside of the workplace, a fact overlooked by those who think everyone has the same goals.

Norma retired in 1985 and read avidly, knew her current affairs (foreign policy a speciality) and enjoyed television and her cat. Housework and cooking however did not feature in her daily routine if it could be helped. She walked daily almost before the crack of dawn with a neighbour for an hour. Norma’s GP for many years, local identity Dr. Jack Goldberg, was one of the few people she took any notice of. He told her “Norma, if you don’t walk, you won’t be able to.”

I think Norma’s working years were just focused on putting one foot in front of the other going to full-time work 48 weeks of the year. Any spare time was her own and she wasn’t about to share it with anyone assuming that she had any spare energy to do so.

Fast forward to 2006, she very reluctantly left Garden City and joined her brother Bob in Vasey RSL Care’s ANZAC Hostel in Brighton. Norma enjoyed the companionship and stimulation of others despite being irritated by other people “in my house”. Her sharp tongue was in evidence as brother and sister had the occasional childhood-type squabble played out in their eighties.

Norma was a product of her time, class and gender – having to work, leaving school earlier than she would if she had been born into the middle class and earning less than a man doing a commensurate job. She never drove a car (her father thought this was a boon to other motorists) and her transport world consisted of the bus. She did this for 45 years of her working life. She had the occasional interstate holiday and always paid cash or went without. This lifestyle would seem unacceptably stultifying to the modern woman but Norma was very much a modern woman within her class and the general constraints of society at the time.

Norma died at age 96 in the care of Vasey RSL Brighton East.

You can read more about the Watters family in Captain James Renton Watters – The Truth.