Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Melbourne’s Sewer Mains in Port Melbourne

Instalment 3 of 3. The “Hobson’s Bay Main”

by Richard Olive

A previous instalment in this series described how sewage flowing towards Port Phillip Bay from the eastern suburbs was intercepted by the Hobson’s Bay Main, and redirected through Port Melbourne towards the Spotswood Pumping Station.

Initially, in the 1890s, the main started at Fraser Street in St Kilda, but it was soon extended to Brighton then to Sandringham. It was tunnelled for virtually the entire distance. The portion within Port Melbourne / Fishermans Bend was carried out under three separate contracts, executed simultaneously to expedite completion. The contracts were let towards the end of 1893 and were all completed before the end of 1896.

| Zone | Extent | Length | Diam. | Contractor | Cost L/s/d |

| 1 | Under Yarra | 1782 ft (543 m) | 9’ 0” (2.74m) | A T Robb/ A G Shaw | 48,801/14/3 |

| 2 | Yarra to PM Tennis Club | 10162 ft (3097 m) | 8’ 9” (2.67m) | James Moore | 104,262/19/11 |

| 3 | PM Tennis to Foote St | 4872 ft (1485m) | 8’ 6” (2.44m) | A G Shaw | 69,708/17/1 |

In essence, the tunnel runs under Graham Street, past Gasworks Park, across Bay Street and under the light-rail route. At Ross St it receives the Melbourne Main (refer Instalment 2), before deviating to run along the length of Garden City Reserve, then Howe Parade, across Williamstown Road, under the southern goal square of Melbourne Grammar School’s Edwin Flack Oval, and finally along beside the West Gate Bridge and under the Yarra to the old pump station, now Science Works Museum.

For most of this route, the tunnel is about 16 metres below the surface, and it runs continuously down grade, dropping about half a metre every kilometre. For the entirety of the 5+ kilometres through Port Melbourne the geology consists of alluvials, i.e. sand and silt, always saturated with ground water under pressure from either the bay, the river or swamp ponds on the surface. The alluvium, which stretches from Albert Park to Spotswood has resulted from millennia of deposition as the Yarra has weaved its course. Interestingly, somewhere across the Fishermans Bend flats (Zone 2 in the above table), the tunnel penetrated an old river course, characterised by porous gravel deposits and by fallen trees along the banks, which were still recognisable after countless thousands of years. Even worse, opening of the tunnel released foul-smelling noxious gasses. Chief Engineer, William Thwaites, reported that the gas “had a very strong smell, and affected the eyes of the workmen, causing extreme pain, and blinding them for a time, to the extent that some of the men had to be led home after work.”

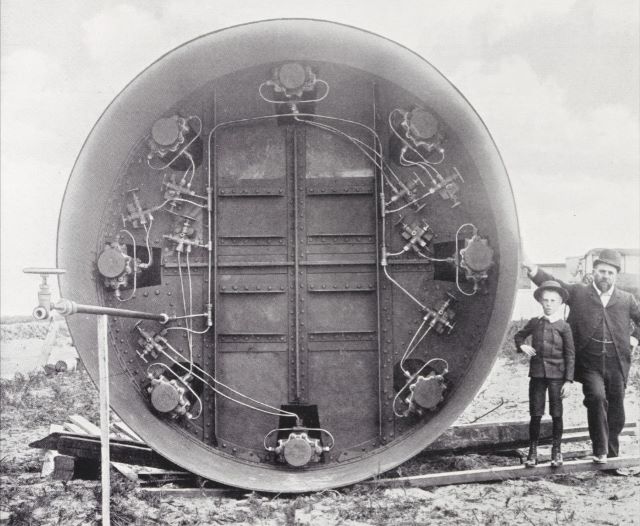

Note the absence of hard-hats and safety clothing, poor lighting and manual tools

Maybe it is contrary to the intuition of many readers, but difficulty in tunnelling is often exacerbated by small diameter and by soft ground. The former makes working conditions very congested, while the latter poses the constant risk of collapse. Both factors were at play in the Hobson’s Bay Main. It must also be remembered that in the 1890s there was no mechanised excavation equipment. All soil had to be removed by manual labour, using pick and shovel.

The ground was so weak along virtually the entire length of Graham Street that numerous subsidences in the street occurred, even to breakouts in the surface of the roadway. Conditions were at their worst under the railway line, i.e. where the current overpass crosses the light rail line. This is near the junction with the Melbourne Main, at the bottom end of Ross Street. We have already read in Instalment 2, of the treacherous ground conditions in that vicinity.

Given the weak soil, the high ground water pressure and the novelty of the construction procedures, it is something of a wonder that no serious accidents occurred along the 4.5 kilometres from the Yarra to Albert Park. It was in the crossing beneath the Yarra, that tragedy was to strike. A modern-day civil engineer would say that it was a disaster waiting to happen. Only 11 feet (3.4 metres) of soft silt and sand existed between the bed of the river and the crown of the tunnel. The headlines of an extensive article (appended below) in The Argus on 13 April 1895 provide a neat summary on the incident:

APPALLING ACCIDENT: COLLAPSE OF A SEWER

AN ENGINEER AND FIVE WORKMEN DROWNED

IMPRISONED IN THE AIRLOCK

NO CHANCE OF ESCAPE

THE BODIES NOT RECOVERED

Contractor Robb was relieved of his responsibilities and completion of his contract (Zone 1) was handed to A.G. Shaw, who had just completed Zone 3. Although the difficulties persisted, somehow Zone 1 eventually linked up with Zone 2, and the Hobson’s Bay Main was complete. As reported in Instalment 1, on 17 August 1897, patrons of Port Melbourne’s All England Eleven Hotel were the first to find relief in the new sewerage system.

By way of update, the tunnel beneath the river was replaced in the 1960s, primarily to allow for dredging of a deeper waterway up the Yarra. The original crossing was abandoned. And currently, that replacement tunnel of the 1960s is being duplicated, to provide for increased capacity and easier maintenance. Meanwhile, the brick-lined tunnels of the 1890s from Fishermans Bend to Albert Park continue to serve us, essentially in original condition, albeit with some repairs here and there.

Some Observations in Retrospect

Technologically, the work was a huge achievement by the nascent MMBW, not only for its novelty, its complexity and its risk, but also for the challenge of managing such a plethora of contracts simultaneously. Remember that the sewer mains in Port Melbourne were not the only ones; the network was being constructed right across the entire metropolitan area. Thousands of kilometres of reticulation from every home, and intermediate service sewers, were constructed in trenches by the MMBW’s own labour forces. The mains were deeper and were tunnelled, and were constructed by contractors under MMBW’s supervision. We can presume that both the MMBW and its contractors recruited unskilled labour locally, and would have included many old denizens of the Borough. Do any members of PMHPS know of examples among their forebears?

Although the MMBW rightly deserves huge credit for the achievement, plaudits are also due to the workers, at an individual level. They seem to have been overlooked in the scant written history. For those who are not familiar with tunnelling work, it is probably difficult to imagine just how terrible their working conditions were. Adjectives which spring to mind are: dangerous, congested, back-breaking, ill-lit, suffocating, sodden, muddy, and dirty. And as the pictures attest, they wore nothing in the way of protective headgear or clothing. Their leather boots would not have kept their feet dry. The lack of gloves inevitably led to blisters, bruises, cuts and abrasions. In short, these men were unheralded heroes.

Paris has its Eiffel Tower, New York has its Statue of Liberty, both structures more-or-less contemporaneous with our sewer system. Celebrated though they are, and rightly so, as engineering challenges they are no more remarkable than our sewerage system. Yes, one can understand the citizenry not singing the praises of our sewer, but frankly we seem unaware of the importance of it, even of its existence. The Hobson’s Bay Main now serves 30% of the populace on Melbourne, say 1.5 million people, and yet casual conversations along Howe Parade suggest that the residents are largely unaware of its existence. Why? Well, the dreadful detritus of a million and a half bladders and bowels does not bear thinking about. Certainly a case of out of sight, out of mind.

Acknowledgements: The writer acknowledges the assistance of the following engineers from Melbourne Water: Paul Balassone, Alex Chesterman and Peter Clark

References

Thwaites, William. Sewerage System

Dunlop, George Harvey. Hydraulic Shield Tunnelling in Melbourne.

Both of the above papers appeared in the Special Edition of the Building, Engineering and Mining Journal. 1905.

Extract from The Argus, 13 April 1895, page 7.

APPALLING ACCIDENT: COLLAPSE OF A SEWER

AN ENGINEER AND FIVE WORKMEN DROWNED

IMPRISONED IN THE AIRLOCK

NO CHANCE OF ESCAPE

THE BODIES NOT RECOVERED

An accident by which, with almost the speed of thought, six men were deprived of their lives, took place at the Metropolitan sewerage works at Spottiswoode yesterday evening. Messrs. A. T. Robb and Co. have a contract at that place for a section of the main sewer which passes under the River Yarra, and there at 8 o’clock yesterday evening five men were at work extending the tunnel, with Mr. Robb’s engineer superintending the operations, and – to describe the tragedy in the briefest possible terms – the river flowing over their heads broke into the tunnel with a suddenness which left no chance of escape, and they were drowned. Their bodies remain in the hole which proved their death-trap, and there is little immediate prospect of their recovery.

The tunnelling work was not suspended yesterday though it was a public holiday, for work of such a difficult and important character cannot be lightly delayed. The task of boring under the bed of the river has proved a more difficult one than was anticipated. The borings made into the bed of the stream before the works were let seemed to indicate that sound and easily worked material would be encountered. A shaft was sunk 61 ft., and then the work of driving a tunnel 11 ft in diameter was undertaken. The ground proved to be sandy and treacherous, and it was soon found that all the resources of engineering would be required to carry the work to completion. When about 400ft. of tunnel had been driven an air-lock was constructed. This consists of a strong brick chamber built across the tunnel, into which compressed air is pumped from the engine on the surface, and compressed air is also supplied to the face beyond this, in which the men work. The compressed air is used to hold up the face of earth and to keep the water back, and the air lock is used to allow transit from the shaft to the face where the men work. When the pressure of the air in the lock equals that in the face the door between the two opens. When it is necessary to pass from the air-lock back to the shaft the iron door communicating with the face is closed and the pressure is thus maintained there. The men work inside an iron shield, which is driven forward by hydraulic pressure. Inside this shield a casing of iron is constructed in sections of 2ft. 9in. at a time, and inside this there is one foot of brick and cement built.

At 3 o’clock yesterday afternoon five men went on shift, and Mr. Buchanan, the engineer superintending the works for Messrs. Robb and Co., was with them nearly the whole of the afternoon. At half-past 7 Henry Hoard, a fitter, who erected the iron plates into their position left the face where the men were working, and passed into the air-lock in order to get a further supply of plates. Mr. Buchanan was then with the men in the face. He obtained the plates from the shaft, and was assisted by a man named Williams to push the trolly on which they were placed in the air lock.

They were accompanied by Mr. Watson, an inspector for the Metropolitan Board of Works. Having got the iron plates into the air lock the door leading to the shaft was fastened, and the air was turned on to the lock in order to raise it to the same pressure as that in the face. Hoard turned the handle so as to leave the door free to open when the necessary pressure had been obtained, there being at that time no appearance of anything wrong with the men in the face. There is a small pane of thick glass in the door so that the men can see from one place into the other. When the air had been raised to half the necessary pressure Hoard saw one of the men who were working in the face code to the door and turn the handle,. He attached little importance to this though he called the attention of his mate to the circumstance. Shortly afterwards he saw Mr Buchanan standing before the glass with a candle in his hand and beckoning as if something was wrong, but almost before he had time to realise this there was a rush of water which put out the light, and then all was over. The men in the air lock at once conjectured that the river had burst in on their comrades the other side of the door, but nothing – absolutely nothing – could be done to help them. At the time when Mr Buchanan made his signals for help the air-valve was fully opened, and the pressure in the airlock was being raised at the greatest possible speed. The door could not have been opened until the pressure was equal on both sides of it, and when the water rushed in and filled the excavation of course it was quite impossible to move it. Even had it been possible, the water would then have rushed into the tunnel, and the whole of the men would have been drowned.

The engine was kept at work till a late hour last night still pumping air down, though it is beyond the bounds of hope that any of the men can have survived, but nothing else has been done, or can be done, for the present. It will not be possible to reach the men who have been drowned through the tunnel. Efforts may be made to recover their bodies by diving and if this is not successful then the only other method is to erect a cofferdam in the river.

There was very little excitement at the scene of the accident last night. About a score of men had gathered round the shaft, and were conversing in subdued tones. About half past 10 an elderly woman came down and inquired the names of the men who were drowned. Then the name Johnson was mentioned she gave way to passionate grief, and it was conjectured that she is the mother of the man mentioned, for he is unmarried, and his mates were aware that he was the support of a widowed mother.

Mr. John Buchanan, who is one of the victims of the accident, has been connected with Messrs Robb and Co’s railway works in Queensland. He was about 36 years of age, a widower, with one child. The other men who perished were as follows:

James Burke, the boss of the shift, a single man, about 25 years of age.

Thomas Johnson, the man already referred to.

Martin Gabriel, a married man, about 45 years of age.

Joseph Jackson, a young man, unmarried.

William Foster, a married man.

The last named has only been at the work for a fortnight.

At the place where the accident occurred the tunnel was immediately under the centre of the river. There is supposed to be about 11 ft. of earth between the top of the bottom of the river. About 3 ft. of the material in the top of the tunnel is a sandy clay, below that there is from 2ft. to 2ft. 6in. of drift sand, and then again comes the sandy clay. There has been always a considerable leakage through the face, but it was felt that to put on a very high pressure of air in order to effectually stop this would be dangerous, as the pressure might burst through the loose strata into the bottom of the river, and therefore very great care was necessary in regulating the pressure. That the compressed air did find its way into the river was evidenced by the bubbles which were continually rising to the surface above the tunnel, but whether the accident is due to too great pressure of air or to the river percolating through the loose strata and gradually making a hole through which the fatal rush followed can never be determined.