The War in Port – 1917

As we make final preparations for Christmas . . .

On the 20th December 1917 men and women in Port Melbourne voted in a referendum on this question

“Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the Australian Imperial forces overseas?”

This question, although it does not use the word conscription, came to be known as the conscription referendum of 1917.

Recently someone said that local history is like a pincushion. This observation well describes the density of activities and experiences related to the war in the second half of 1917 in Port.

In the weeks leading up to the vote, several anti-conscription rallies were held in Port – at the Town Hall, the Port Picture Theatre and outside the Fountain Inn where a crowd of 300 was reported. A ‘snow storm’ of highly emotive leaflets were distributed by pro and anti-conscriptionists.

Earlier in the year, Prime Minister Billy Hughes had traveled to England where the gravity of the situation on the western front was impressed upon him. Through 1917, the battles at Bullecourt, Messines, and the third battle of Ypres resulted in catastrophic loss of life. Reinforcements were badly needed. Hughes returned home determined to press the issue of conscription even though he’d spoken against it earlier, and even though the 1916 referendum had been defeated.

It was against this background that Hughes announced the referendum on 7 November. And so began ‘a public debate that has never been rivaled in Australian political history for its bitterness divisiveness and violence.’

Alongside the conscription referendum was the issue of food prices. Since the start of the war, food prices had risen by up to 28%. Frozen meat as well as Australia’s wheat export crop had been committed to Britain. However, a shortage of shipping meant the food piled up at railway sidings where the mice and weevils ‘began their phenomenal depredations’. Throughout August and September crowds in their thousands gathered on the Yarra River bank protesting against food prices. The wharf labourers had been on strike since August, refusing to load food for shipment overseas when it was so badly needed at home.

Earlier in the year Adela Pankhurst had campaigned on food prices at the Port Picture Theatre

“The time has come for women to do more than knit, knit, knit. It is time for women to say this is ENOUGH!

At the end of November, she was jailed for four months at Pentridge for defying orders not to campaign in public.

On 24 November, 1,073 wounded soldiers from those battles on the western front returned to Town Pier at the end of Bay Street where the Womens Welcoming Committee met them with cigarettes and fruit.

Voluntary enlistment was flagging. Special sergeants were appointed to crank up the recruitment effort. Recruitment meetings were held at lunch time at workplaces around Port. Sometimes the meetings would be addressed by returned soldiers.

Rouse Street was dense with activity related to the war.

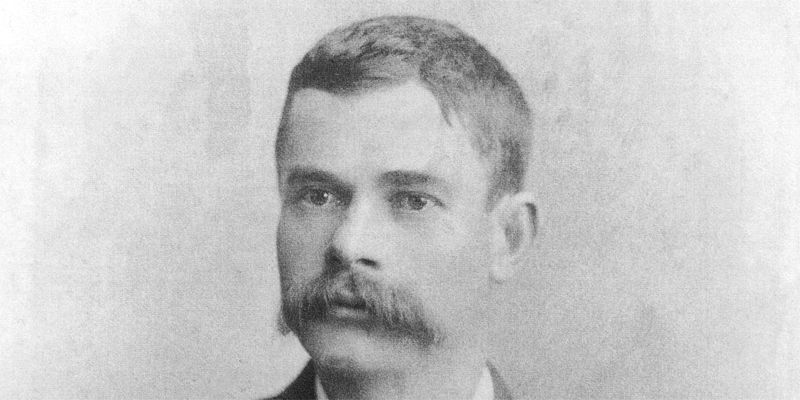

Many employees of the large Swallow and Ariell biscuit factory had enlisted as well as proprietor Frederick Derham’s son. Employee Miss Elsie Holmes had organised fellow workers into the the phenomenally productive Busy Bees. By November 1917, they had sewn 4,939 “good luck” shirts, 1,545 leather cardigans, 23,461 cardigan handkerchiefs, 1,474 pairs of knitted socks as well as other items.

The flag at Swallow and Ariell flew at half mast when news was received of the death of former employees Private Thomas Lovell and Private John Thompson – an only son.

Nearby at 242 Rouse St, the Freame family learned that their son Edmund, known as Tom, had been killed in action in Belgium on 20 September. He had been an athlete and a good runner. The notice in the Port Melbourne Standard on 10 November said

Our darling boy.

We pictured his safe returning, but God ‘s will alters all. R.I.P.

Just across the road Charles James from 193 Rouse St enlisted on 5 November. He was to embark on HMAT Ulysses just a few days later on 22nd December.

In another household in Rouse St, tailoress Janet Adams boarded with the Bellion family. She was utterly opposed to the war believing it to be a capitalist conflict driven by the colonial rivalries of the European nations. She shared her beliefs with young Ada Bellion who became a life long pacifist.

Port would still have been reeling following the murder of Annie Samson on 19 October at the hands of her foster brother-in law and Gallipoli veteran, Joe Budd. Samson had been an organiser for the ‘No’ campaign in 1916 and it was partly her support for the wharf labourers on strike that prompted Budd’s murderous jealousy.

At the Port Town Hall there was a fundraising event nearly every weekend. In the lead up to Christmas, parties were held for the families and children of soldiers. Mayor J. P. Crichton had a son at the front, as did Town Clerk Crockford. The Town Hall was also where men enlisted.

All these activities took place against the background of civic improvements with electric light introduced into homes and businesses in 1917.

And how did Port vote?

YES 1,256 NO 3,431

More

Walk the war in Port

Visit the excellent exhibition at the Old Treasury Building A Nation Divided: The Great War and Conscription

Thanks to David Thompson who reads the 1917 papers every week to post the news on Facebook (www.facebook.com/portmelbfirstworldwar100/). It is out of his work that this synthesis has been prepared.