Allan Whittaker Commemoration 2013

Port in the twenties – a difficult, suffering place

Former Supreme Court Judge Frank Vincent spoke about Whittaker in the Port Melbourne and wider social and political context of the late 1920s. Here is a transcript of his speech:

“Port Melbourne in the twenties was a place of considerable poverty. It was a place where men were engaged in what was regarded as the most menial of labour possible in the community and the area was regarded as one of those to which no one would ever aspire.

The depression hit early in Port Melbourne and it hit very hard, and it hit particularly the members of the two waterside worker unions that operated in this region. They both suffered because there were reducing cargoes well before the depression actually was recognised and there was a militant effort by shipowners to reduce the conditions under which they had to work and live at that time.

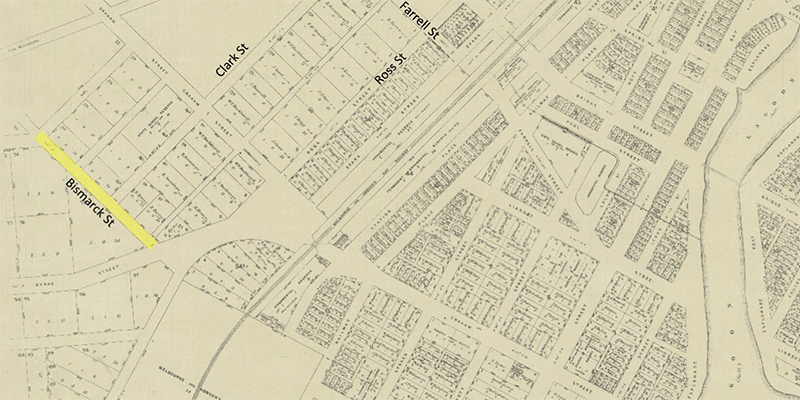

So it was of its very nature a very difficult and increasingly difficult environment for them. The men who gathered at Hogans Flat had been waiting for a vessel to arrive so that they were eligible for the pick up. There was a real effort at that time by the shipowners to have the pick ups conducted twice a day so that you had to be available virtually all of the time.

The men who came down on the 2 November had been assembling for four successive days without being picked up at all. Among them was Allan Whittaker.

Allan Whittaker was not a well man. When he was subsequently admitted to hospital following receipt of the gunshot that actually killed him, he was described by the doctors as underweight and malnourished. The people here were very close to starving, and he was one of them.

Although there was anger and there was violence among the men who gathered that day, and that can’t be put to one side, there was a very different level of violence employed by the police. And of course Whittaker was not a man himself who would have been involved in any of the violent acts because he simply would not have been well enough. Apart from anything else, he limped fairly badly because of the gun shot that he had received at Gallipoli some twenty odd years earlier.

So picture it.

Here’s a man malnourished, underweight and on the only accounts that we have of what occurred at the time he was standing on the extreme edge of the group and to the rear. He was shot. He was shot according to the coronial inquiry from the front. That is highly unlikely to have been the case. Only a very very poor inquiry was ever conducted into that matter. This was not a shooting by the police that the authorities wanted investigated genuinely at all. So he never achieved justice during his lifetime and only very limited recognition in the years to follow.

But his story, and who he was, and what happened on that day impacted very powerfully upon the Port Melbourne community. Now I was born into that community only eight years afterwards, and it was still a poor difficult and suffering community at that stage. It was a place of considerable poverty. And of course I was born into a waterfront family.

But the remarkable thing about what occurred at that time, and which is not simply the story of one man, is that there was a bonding, a linkage between those people who remained with the Waterside Workers Federation in the very very difficult period of almost twelve years that followed that particularly shooting. Because quite a few defected. Quite a few left the industry entirely.

Those that remained, those that lived in this area of Port Melbourne, formed a very very powerful community and a community that had its effect right across our industrial scene for the many years that followed.

I don’t think anyone should underestimate the significance of the struggles which occurred at that time. The courage that it took for men and women to hold together when they could easily have joined a scab union and defected and given away their principles and given away their community.

But they didn’t do that. And it took a very special kind of courage and it ought to be memorialised, it ought to be understood, we ought to be inordinately proud of it.

There are lots of things in our Australian history of which we should be massively ashamed – some of them are occurring at the present time – but this is certainly not one of them.”